Great expectations and generous reading of guidelines underestimate potential risk in oversight of COVID-19 pro-vaccine quality, safety testing, and manufacturing: 248 questions for FDA

David Wiseman, 1 L Maria Gutschi 2

1 Synechion, Inc., Dallas, TX 75252

ORCID: 0000-0002-8367-6158

2 Pharmacy Consultant, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

ORCID: 0009-0008-0020-0826

Version: 091325

Funding: No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest: DW has acted as an expert witness or consultant in several legal cases related to parental authority regarding COVID-19 vaccines or their mandatory use.

Data availability: This is a review of the published medical and scientific literature, including regulatory documents released publicly of through FOIA requests.

ABSTRACT

Background

On December 6, 2023, Florida Surgeon General Ladapo wrote to the then FDA Commissioner and CDC Director Cohen of CDC, raising concerns about the COVID-19 pro-vaccines, particularly related to DNA contamination and the presence, in the Pfizer product, of an SV40 promotor-enhancer-ori sequence. These findings were confirmed by a number of labs, by regulators, or documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

A response was furnished by FDA, which formed the basis for subsequent responses to questions regarding DNA contamination and other manufacturing and safety testing issues, including frameshift proteins.

Method

This document is written in the form of a point-by-point critique to this response, with several additional issues identified. Along with explanatory text, this document contains 248 questions to FDA.

Findings

The safety standard for an EUA requires that “the known and potential benefits of the product, […] outweigh [its] known and potential risks. “ Uncertainties, irregularities, or deviations from normal accepted practice in the manufacturing process represent “potential risks” FDA was required to consider. It was not necessary to prove that DNA contamination, the SV40 sequence, or frameshifted proteins did caused harm, the mere fact of these phenomena constituted an uninvestigated potential risk FDA was legally required to consider when granting the EUAs.

Given the rapid launch of the COVID-19 pro-vaccines, manufacturing and safety testing standards needed to be tightened, not loosened as described here, adding potential, if not actual risk.

Generous interpretation of various guidelines, and the word “expects” has been used by both sponsors and regulators to justify why a certain test should not be done or a safeguard implemented, without providing detailed justification supporting the assertion.

We detail a number of inconsistencies with statements made by regulators and data obtained from public records, in one case we found an instance of an undeclared (by regulators) genotoxicity study.

The developmental and regulatory failure that the findings related to residual DNA and frameshift proteins represent, are hardly evidence that these modRNA vaccines meet “ rigorous scientific standards,” and will no doubt erode further the trust in public health institutions.

Conclusion

We hope that our questions will allow us to understand the potential harms associated with the modRNA pro-vaccines in a way that begins to restore the public trust in the scientific process and health institutions, by engaging in a process of introspection and improvement of regulatory processes and decision-making.

These expedited and still experimental vaccines are the most complicated medical products ever deployed. Pfizer’s recently retired head of vaccine research, Dr. Kathrin Jansen, was quoted in Nature as saying ““We flew the aeroplane while we were still building it.” It is now time to ground the plane pending the answers to these, and no doubt, many more questions.

Keywords: Vaccine, COVID-19, Pfizer-BioNTech, Janssen, Moderna, vaccine safety, vaccine manufacturing, mRNA vaccine, DNA contamination, FDA, CDC, genotoxicity, mutagenicity

Table of Contents

2.1. Off-label claims related to serious outcomes . 5

2.2. Off-label claims related to pregnancy and lactation . 6

3. “Context of the manufacturing process” . 9

3.1. Manufacturing process changes – what was disclosed and what was promised? . 9

3.2. Was the descriptive analysis performed? . 12

3.3. EMA concerns regarding the Pfizer process and the process change . 13

3.4. EMA concerns regarding residual DNA . 14

3.6. Formulation and process changes after nonclinical studies . 17

4. Why are the possible harms from residual DNA? . 18

4.1. Prior downgrading of integration risk for residual DNA . 18

4.2. Risk of chromosomal integration: nuclear access of DNA .. 19

4.3. Additive risks of integration by residual DNA and by DNA reverse transcribed from modRNA . 22

4.3.1. “the mRNA is destroyed” . 22

4.3.2. “the RNA can't get into the nucleus, the nucleus has a one-way valve” . 22

4.3.3. “our cells do not have the enzyme necessary to get RNA back into DNA” . 23

4.4. The need for integration studies . 24

4.5. Risk of episomal / extrachromosomal expression . 26

4.6. Non-integrating mechanisms of DNA toxicology . 26

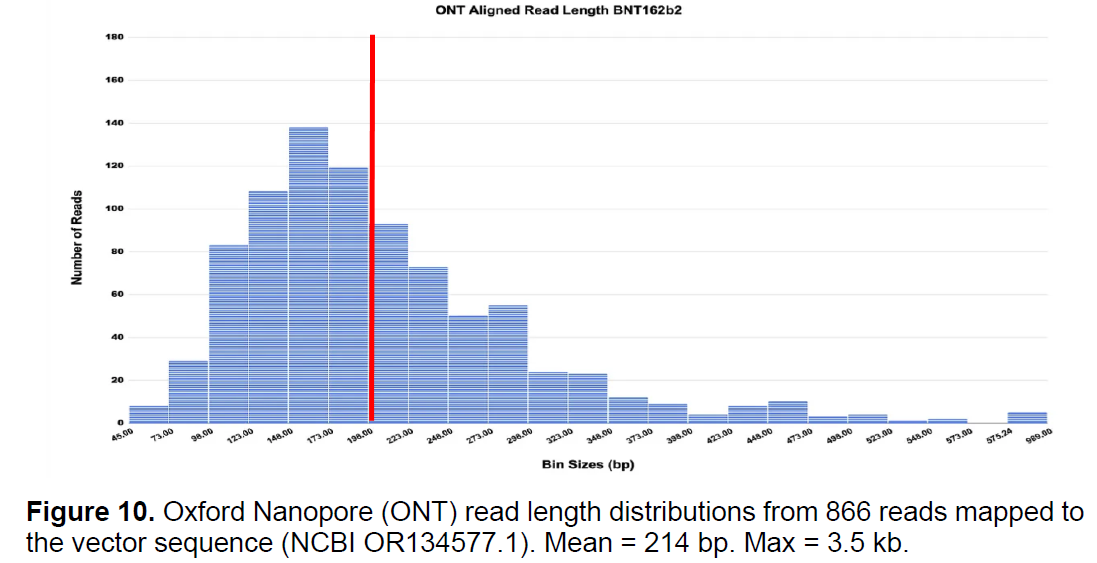

5. Experimental findings regarding residual DNA . 27

6. What are the guidelines concerning residual DNA? . 28

6.1. Guidelines on amount of residual DNA . 28

6.2 Guidelines on additional considerations for amount of residual DNA . 29

6.3. Guidelines on measurement of residual DNA . 30

6.4. Guidelines on fragment size of residual DNA . 31

6.4.1. What do the guidelines say about fragment size of residual DNA? . 31

6.4.2. Is fragment size of residual DNA being measured? . 32

6.4.3. Fragments of residual DNA exceeding the 200 bp guideline have been reported . 33

6.4.4. Concerns regarding residual DNA fragments smaller than the 200 bp guideline . 34

7. Concerns regarding intact plasmid sequence elements . 35

7.1. Antibiotic resistance gene . 35

7.2. SV40 promoter-enhancer and other sequences . 36

7.2.1. Concerns about specific SV40 sequences and SV40 proteins must not be conflated . 36

7.2.2. Possible consequences of the SV40 enhancer-promotor-ori sequences . 36

7.2.3. Was the SV40 and other sequence and other sequences identified to FDA? . 36

7.3. Unintended sequences in DNA plasmid vector 39

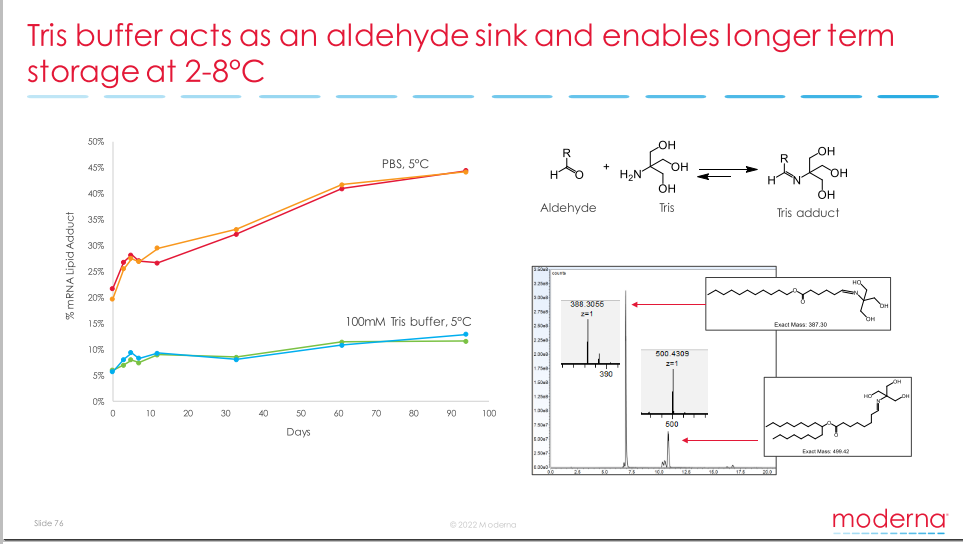

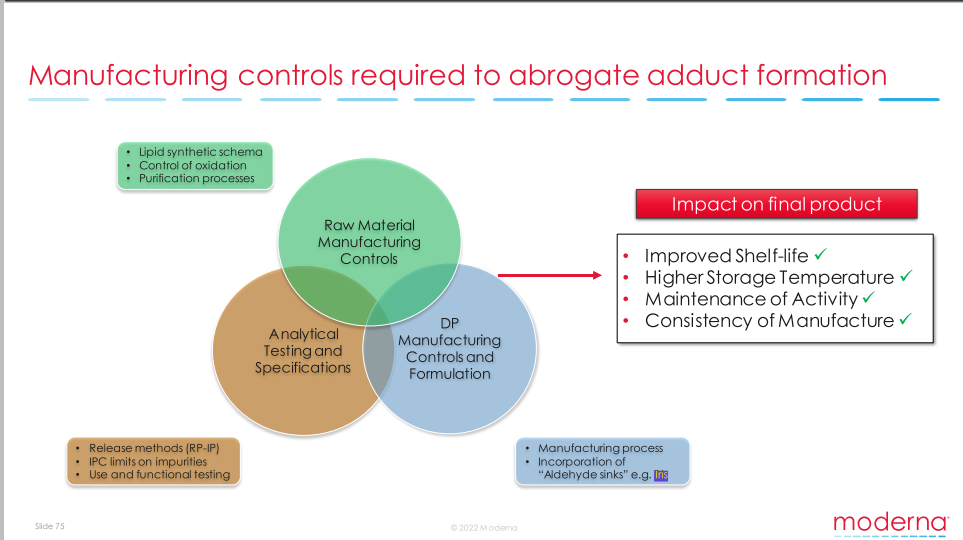

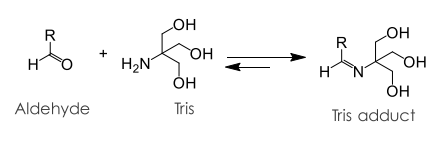

8. RNA or DNA Lipid Adducts, “Process 3” . 40

8.1. Formation of RNA or DNA Lipid Adducts . 40

8.2. Process 3: Pfizer buffer change . 42

9. Novel heterotrimers in bivalent pro-vaccines: Process 2 for Moderna, Process 4 for Pfizer 43

10. Safety studies with modRNA “and lipid nanoparticle together that constitute the vaccine” ? . 44

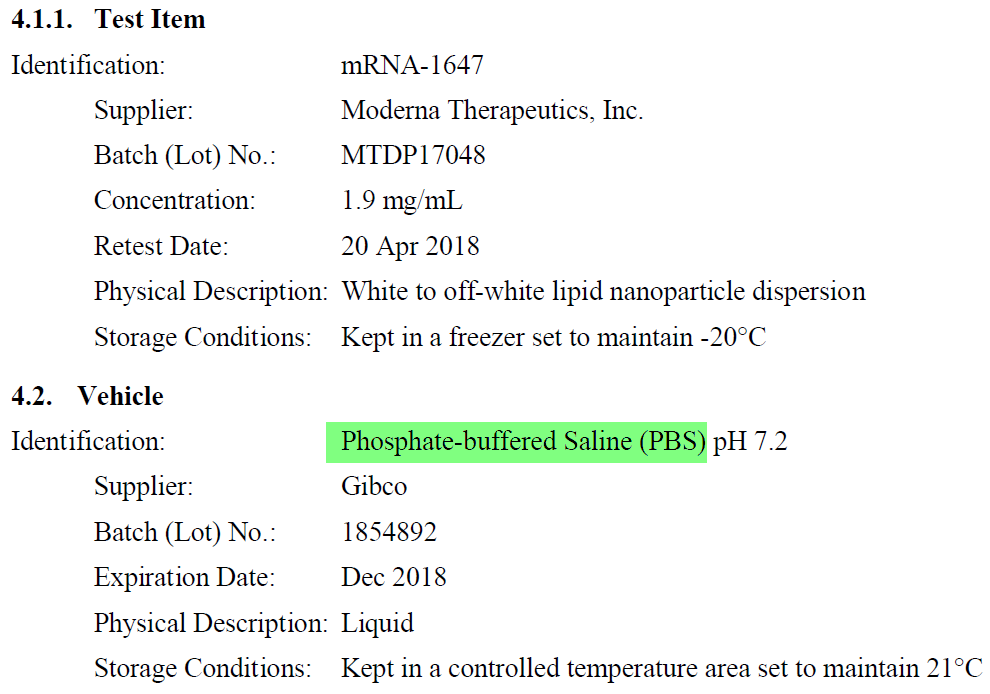

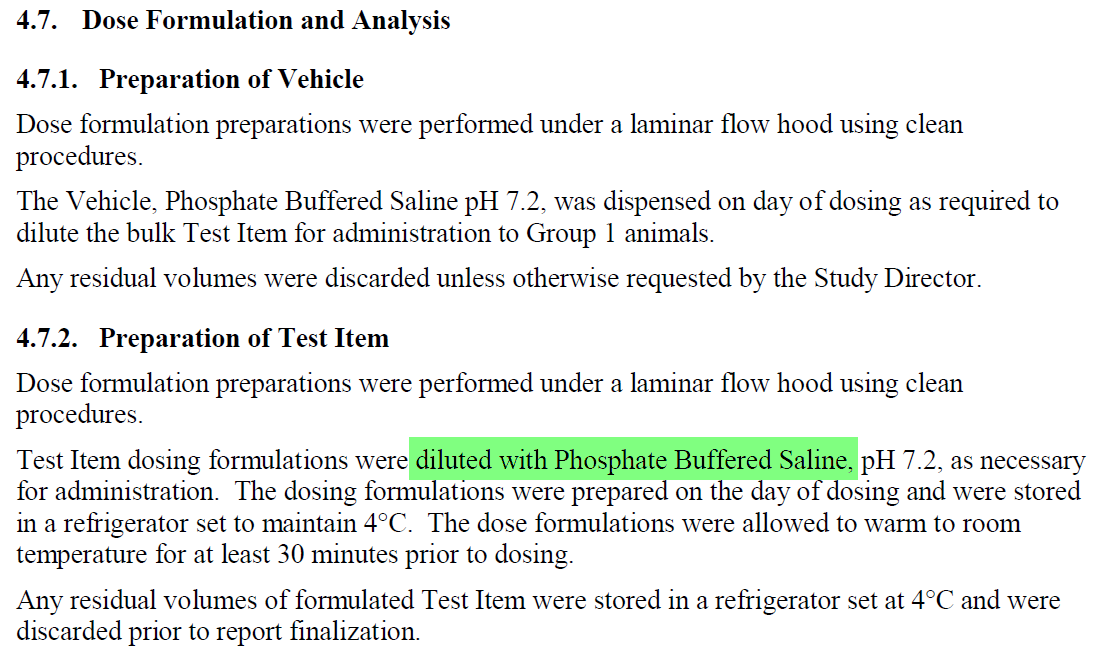

10.1. Which formulations were used in Moderna’s nonclinical safety studies? . 44

10.1.1. Was the modRNA that “constitutes the vaccine” used in genotoxicity studies? . 48

10.1.3. Was LNP size comparable in Moderna’s safety studies? . 49

10.1.4. Other differences in manufacturing and formulation of mRNA 1647 used in the PK study . 50

10.1.5. Inadequate preclinical use of animals with spike-ACE2R binding relevant characteristics . 51

11. Inadequate studies failed to predict modRNA and spike protein PK and expression kinetics . 52

11.1. Discrepancies between messaging and data on modRNA, spike persistence and distribution . 52

11.2.1. Unsupported expectations about modRNA and protein metabolism .. 53

11.2.2. Unsupported expectations about local distribution and action . 54

11.2.3. Unsupported expectation about LNP and mRNA kinetics . 54

11.3. Failure to follow guideline provision for case-by-case consideration . 55

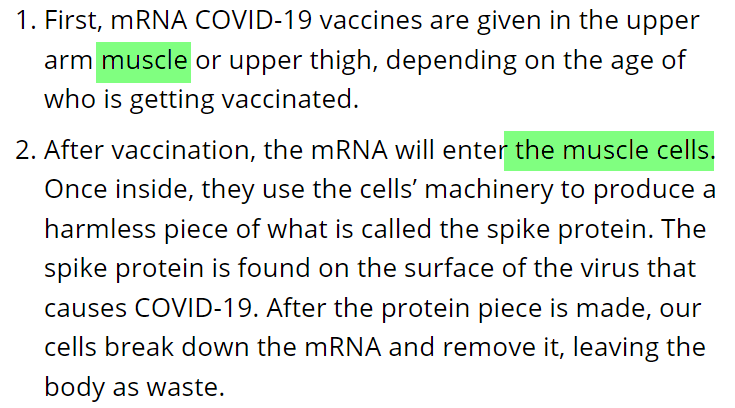

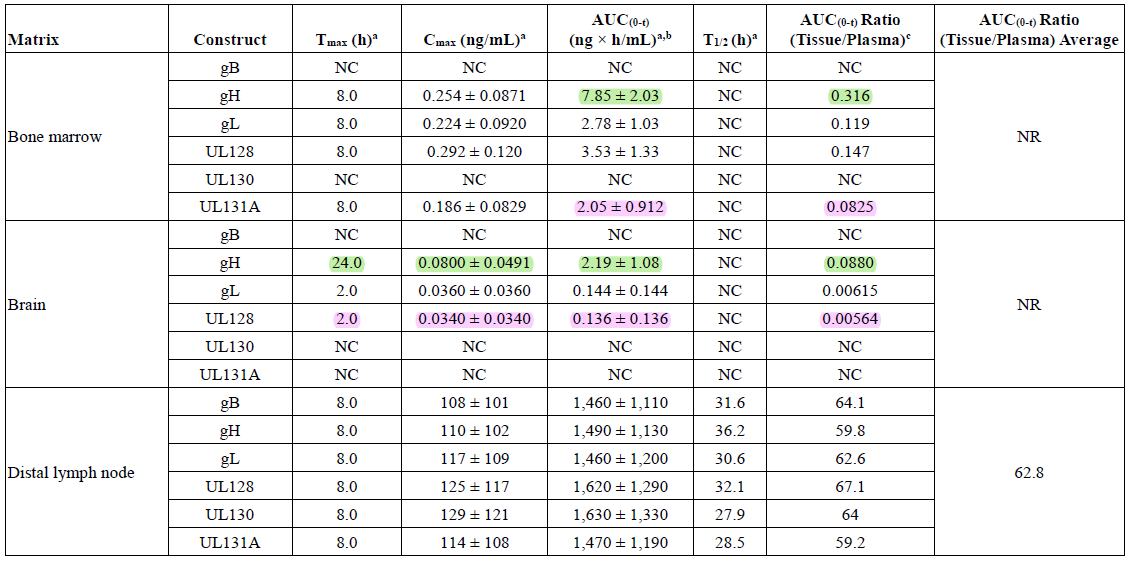

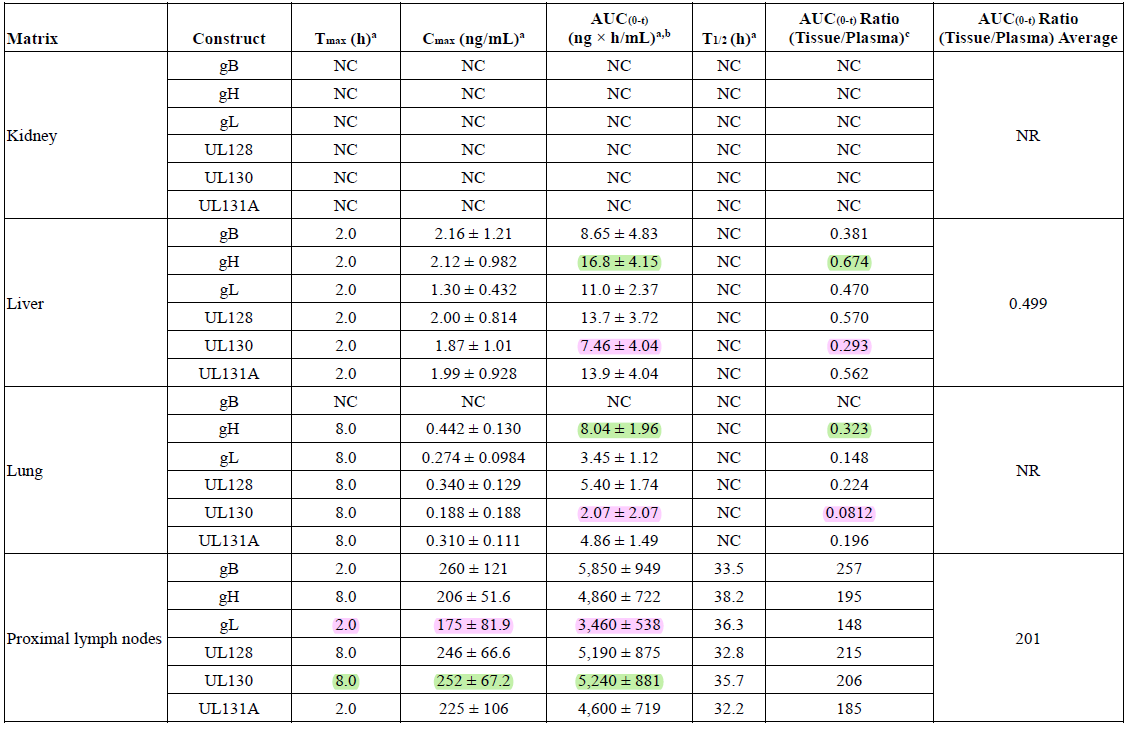

11.4. Superficial analysis of limited biodistribution studies, lacking follow-up: Moderna . 56

11.4.1. Quality and methodology issues . 57

11.4.2. Evidence for mRNA dependent distribution . 57

11.5. Superficial analysis of limited biodistribution studies, lacking follow-up: Pfizer 60

11.6. Biodistribution studies: summary . 61

12. Safety studies: preclinical genotoxicity . 61

12.2. What genotoxicity tests were performed on COMIRNATY or SPIKEVAX? . 63

12.3. What genotoxicity tests were performed on ingredients related modRNA products? . 64

12.3.1. Relevance and reliance on supportive studies involving related modRNA products . 64

12.3.3. Missing genotoxicity studies of SPIKEVAX ingredients or related products? . 65

12.3.4. Questions regarding nonclinical studies other than genotoxicity . 68

14. modRNA vaccines elicit cryptic uncharacterized frameshift proteins of unknown toxicity . 72

15. COVID-19 pro-vaccines meet FDA definition of gene therapy . 76

17. Topics for further discussion . 79

1. Introduction

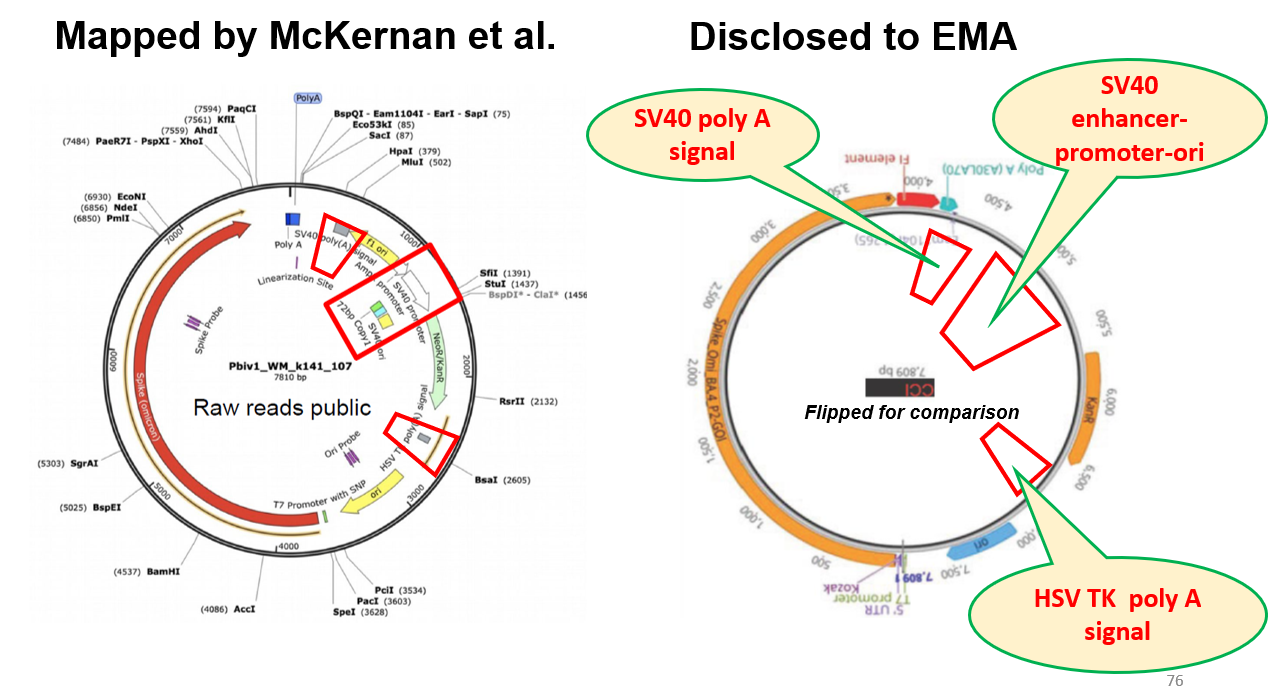

On December 6, 2023, Florida Surgeon General Ladapo wrote (1) to the then FDA Commissioner Califf and CDC Director Cohen, raising concerns about the COVID-19 pro-vaccines, particularly related to DNA contamination and the presence, in the Pfizer product, of an SV40 promotor-enhancer-ori sequence, reported originally by McKernan et al. (2) and expanded upon in a then recent preprint. (3)

A response was furnished on December 14, 2023, (4) by then CBER Director Marks. Rather than allaying his concerns, Dr. Ladapo believed that this response served only to heighten them, prompting Dr, Ladapo to call for a halt in the use of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. (5)

Dr. Marks’ response has formed the basis for subsequent responses to questions regarding DNA contamination since then, despite the confirmation of findings of DNA contamination that exceeded guidelines, and the presence of the SV40 sequences in the Pfizer product. This confirmation has been furnished by laboratories around the world (6-10) and, notably, by high school intern students working under FDA supervision. (11) Further, in numerous FOIA disclosures around the world, regulators have confirmed the presence of the SV40 sequence (including the Marks response (4) ) and the fact that Pfizer had chosen not to specifically disclose this regulatory sequence. Our own unpublished work has confirmed this with the Pfizer 2024-2025 JN.1 formula.

Since the Marks response has formed the basis for FDA’s position on this topic, this document is written in the form of a point-by-point challenge, along with additional points related to safety testing or manufacturing of these products.

Comments are provided on a consolidated point-by-point basis, raising questions in text and provided in list format the end of this document. While FDA is not bound by the actions of regulatory agencies in other countries, by FDA’s citing WHO guidelines as well as “internationally agreed upon recommendations” (4) we are justified in also citing the deliberations of other regulators to inform our expectations of FDA’s actions. Further, in many instances, FDA staff have played a major role in the drafting of various WHO guidelines.

The term pro-vaccine is used here. Unlike conventional vaccines, the modRNA products do not contain target antigens. Rather they contain the genetic instructions that are read by a patient’s body to produce the target spike protein antigen. This is somewhat analogous to the activation of pro-drugs, molecules that lack the desired pharmacologic action, but that are converted by the body to an active form. (12) We employ the term “pro-vaccine” (13, 14) to signify this important distinction, which again has regulatory consequences.

2. Misinformation

2.1. Off-label claims related to serious outcomes

Dr. Marks states: “Given the dramatic reduction in the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness afforded by the vaccines, lower vaccine uptake is contributing to the continued death and serious illness toll of COVID-19.”

The indications stated at the time of Dr. Marks’ response in the package inserts for COMIRNATY and SPIKEVAX read:

“COMIRNATY is a vaccine indicated for active immunization to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in individuals 12 years of age and older.” (15) (and more recently (16) )

“SPIKEVAX is a vaccine indicated for active immunization to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in individuals 12 years of age and older.” (17) (and more recently (18) )

Question 1: Please confirm that neither label includes the indication that the vaccine reduces“the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness” of COVID-19 disease. Q1

Question 2: Has FDA reviewed data that meet the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations” and support the claim that either vaccine reduces “the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness” of COVID-19 disease. Please provide. Q2

Question 3: If FDA considers the data it has reviewed as supporting the claim that either vaccine reduces “the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness” of COVID-19 disease and meeting the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations,” please state whether they do so according to the evidentiary standards set forth in FDA’s 1998 guidance[1](19) or or according to later 2019 (20) and 2023 (21) documents that expand the scope of the types of data that can be used to support certain claims or expanded indications. Q3

Question 4: If FDA has reviewed data that do not meet the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations” but purports to support this claim, please provide the data and state the evidentiary standard such data meet, if at all. Q4

Question 5: If FDA has reviewed data that do not meet the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations” please describe the deficiencies in the data that preclude the inclusion of language asserting that the COVID-19 vaccines reduce “the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness” of COVID-19 disease Q5

Question 6: Please advise whether, in the absence of data meeting the “substantial evidence” standard as well as authorization by FDA of a labeling change to include a claim that the vaccine reduces “the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness” of COVID-19 disease, manufacturers making such a claim would be in violation of statues and regulations regarding off-label promotion? How is your answer influenced by FDA’s draft guidance on Scientific Information on Unapproved Uses (SIUU)? (22) Q6

Question 7: What is the regulatory status of Dr. Marks’ (4)statement regarding a“dramatic reduction in the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness afforded by the vaccines”? Coming from Dr. Marks, a senior FDA official, does this represent an amendment to the approved labeling, a regulatory guidance, an enforcement policy, SIUU, or personal medical opinion? Q7

FDA’s draft guidance on SIUU (22) recommends that in order, inter alia , to facilitate a firm’s obligations to ensure that FDA-required labeling accurately reflects “what is known about the safety profile of the drug,” “to ensure that the FDA-required labeling is not false or misleading,” and to dispel the notion of a “ firm’s intent that the medical product be used for an unapproved use,” (p6/29) sponsors providing SIUU should include, inter alia , “A statement that the unapproved use(s) of the medical product has not been approved by FDA and that the safety and effectiveness of the medical product for the unapproved use(s) has not been established.” (p16/29)

If these sorts of safeguards on the dissemination of SIUU apply to sponsors, who by virtue of their commercial interests, would be suspected by the medical and lay community of what FDA calls “persuasive marketing techniques” (p18/29 in (22) ), then at least similar safeguards and the principles they embody should exist in the case of government health agencies about whom there would be no suspicion.

Question 8: Although this draft guidance applies to sponsors, given Dr. Marks’ statement concerning a “dramatic reduction in the risk of death, hospitalization and serious illness afforded by the vaccines,” and the absence of the corresponding claim in the package insert, is it FDA’s intent that the modRNA COVID-19 vaccines be used to reduce these serious outcomes? Q8

Question 9: Per Question 8, if it is FDA’s intent that the COVID-19 vaccines be used to reduce serious outcomes, would the issuance of such a statement on this use by FDA without the qualifying language concerning this unapproved use, misleadingly imply that this use had been approved by FDA? Q9

Question 10: Did the provision of EUA product to patients who were counseled that these products reduce the risk of death or serious outcomes, violate the provider agreement, which requires that the provider must confine representations to those consistent with the contents of the Fact Sheet - eg (23, 24) ? Q10

2.2. Off-label claims related to pregnancy and lactation

The past and current package inserts for COMIRNATY and SPIKEVAX state:

· “Available data on COMIRNATY administered to pregnant women are insufficient to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy.” (15, 17)

· “It is not known whether COMIRNATY is excreted in human milk. Data are not available to assess the effects of COMIRNATY on the breastfed infant or on milk production/excretion.” (15)

· “Available data on SPIKEVAX administered to pregnant women are insufficient to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy.” (17)

· “It is not known whether SPIKEVAX is excreted in human milk. Data are not available to assess the effects of SPIKEVAX on the breastfed infant or on milk production/excretion.” (17)

Similar language appears in the original versions released in 2021 (COMIRNATY) and 2022 (SPKEVAX).

Question 11: Please confirm that the above excerpts do appear in the respective package inserts. Q11

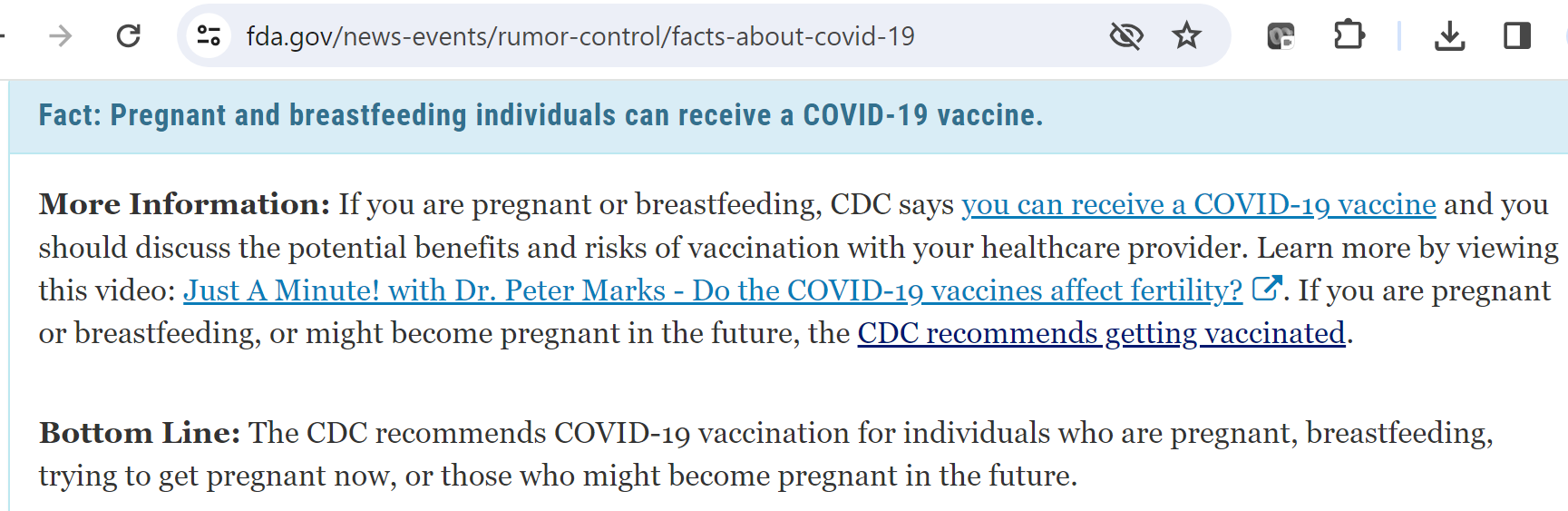

The CDC web site (25) stated:

· “Everyone ages 6 months and older is recommended to get the updated COVID-19 vaccine. This includes people who are pregnant, breastfeeding, trying to get pregnant now, or those who might become pregnant in the future.”

· “ Evidence shows that: COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy is safe and effective.”

· “CDC recommendations align with those from professional medical organizations serving people who are pregnant, including the: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists , Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine , and American Society for Reproductive Medicine ”

Question 12: Has FDA reviewed data that meet the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations” and support the claim that either vaccine is safe and effective for use in pregnancy or lactation. Please provide. Q12

Question 13: If FDA considers the data it has reviewed as supporting the claim that either modRNA vaccine is safe and effective for use in pregnancy and meeting the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations,” please state whether they do so according to the evidentiary standards set forth in FDA’s 1998 guidance (19) or according to later 2019 (20) and 2023 (21) documents that expand the scope of the types of data that can be used to support certain claims or expanded indications. Q13

Question 14: If FDA has reviewed data that do not meet the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations” but purports to support this claim, please provide the data and state the evidentiary standard such data meet, if at all. Q14

Question 15: If FDA has reviewed data that do not meet the standard of “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations” please describe the deficiencies in the data that preclude the removal of tempering labeling language and/or the inclusion of language asserting that the COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective in pregnancy and lactation. Q15

Question 16: Please advise whether, in the absence of data meeting the “substantial evidence” standard as well as authorization by FDA of a labeling change to include a claim that the vaccine is safe and effective in pregnancy, manufacturers making such a claim would be in violation of statues and regulations regarding off-label promotion? Q16

Question 17: Please confirm that CDC’s recommendation for use of the COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy and lactation, along with CDC’s representation that “Evidenceshows that: COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy is safe and effective,” is misleadingly inconsistent with the wording in the COMIRNATY and SPIKEVAX package inserts concerning insufficient data to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy,whether the vaccines are excreted in breast milk, and the lack of data on the effects of the vaccines on the breastfed infant or on milk production/excretion. Q17

Language could not be identified on this CDC web page that refers to the language in the COMIRNATY and SPIKEVAX labelling concerning what is known about the risks of these products in pregnancy and lactation.

Question 18: Please confirm that the absence of prominent language detailing the risks of these products in pregnancy and lactation as described in FDA approved labeling, from CDC’s related recommendations, exacerbates the misleading nature of these recommendations. Q18

Question 19: Please provide the contents and URLs of all current FDA and CDC web pages that discuss the use of these products in pregnancy and lactation. Please detail what steps will be taken to ensure that prominent language will be placed, if currently absent, detailing the risks of these products in pregnancy and lactation as described in FDA approved labeling. Q19

A FDA web page “Facts about COVID-19” (26) appears to endorse CDC’s recommendation as seen in this screen shot. (from 2024)

This page linked to the CDC page cited above (25) as well as another CDC page (27) which described the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines not as “safe and effective” as above but only in terms of a “growing body of evidence … that the benefits of vaccination outweigh any potential risks of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy:”

“Staying up to date with COVID-19 vaccinations is recommended for people who are pregnant , trying to get pregnant now, or who might become pregnant in the future, and people who are breastfeeding. A growing body of evidence on the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination indicates that the benefits of vaccination outweigh any potential risks of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy.” (original links preserved)

The current page states: (28)

“Studies including hundreds of thousands of people around the world show that COVID-19 vaccination before and during pregnancy is safe, effective, and beneficial to both the pregnant woman and the baby. The benefits of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine outweigh any potential risks of vaccination during pregnancy.

FDA’s page also linked to a 47 second video on FDA’s YouTube channel. [2] The video (screenshots below) is dated May 19 2022.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 : Screenshots from May 19 2022 episode of “Just a minute with Dr. Peter Marks.”

YouTube’s “show transcript” feature reads: “ Pregnant or breastfeeding women can certainly receive a COVID-19 vaccine and should discuss the potential benefits and risks of vaccination with their healthcare provider. There is currently no evidence that any vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines, cause fertility problems in either women or men. If you are pregnant or breastfeeding, or might become pregnant in the future, the CDC recommends getting vaccinated. ”

Question 20: Please confirm that FDA’s endorsement of CDC’s recommendation for use of the COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy and lactation, along with CDC’s related representations described above is misleadingly inconsistent with the wording in the COMIRNATY and SPIKEVAX package inserts concerning insufficient data to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy,whether the vaccines are excreted in breast milk, and the lack of data on the effects of the vaccines on the breastfed infant or on milk production/excretion. Q20

There is no language in this video or in the description provided on the YouTube site to alert the viewer to the language cited above appearing in the package inserts for the Pfizer and Moderna products.

To an unprofessional eye, FDA’s video appears well-produced with clear dialog, engaging graphics and an upbeat soundtrack. It is one of a series of over 40 short videos addressing mainly COVID-19 related topics and titled “Just a minute with Dr. Peter Marks.” The series, as its title indicates, develops a celebrity-like status for its featured interlocutor, a senior FDA official, as a means to add authority and credibility to the message, in this case FDA’s endorsement of a CDC recommendation concerning the use of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy and lactation.

FDA’s recent draft guidance on SIUU (p18/29 in (22) ) cited in preface to Question 8 frowns upon the use by sponsors to disseminate SIUU using “persuasive marketing techniques” that could include “the use of celebrity endorsements.” The effective creation and deployment of the Director of CBER as a celebrity persona to endorse CDC’s recommendation for a use characterized by the label as having insufficient data, heightens the concerns expressed in my preface to Question 8 that government agencies have a higher duty to conform to the principles embodied in FDA’s draft guidance on the dissemination of SIUU.

Question 21: Please confirm that the absence of prominent language detailing the risks of these products in pregnancy and lactation as described in FDA approved labeling, from FDA’s written and video endorsement of CDC’s related recommendations, exacerbates the misleading nature of both FDA’s endorsement and CDC’s recommendations. Q21

Question 22: Did the provision of EUA product to patients who were counseled that these products were safe and effective for use in pregnancy and lactation violate the provider agreement, which requires that the provider must confine representations to those consistent with the contents of the Fact Sheet - eg (23, 24) ? Q22

3. “Context of the manufacturing process”

Dr. Marks stated: “ Perpetuating references to this information about residual DNA without placing it within the context of the manufacturing process is misleading.”

We suggest that the statement be revised to read:

“ Perpetuating references to this information about residual DNA without placing it within the context of the change in manufacturing process is misleading.”

Here follows a number of questions about the change in the manufacturing process.

3.1. Manufacturing process changes – what was disclosed and what was promised?

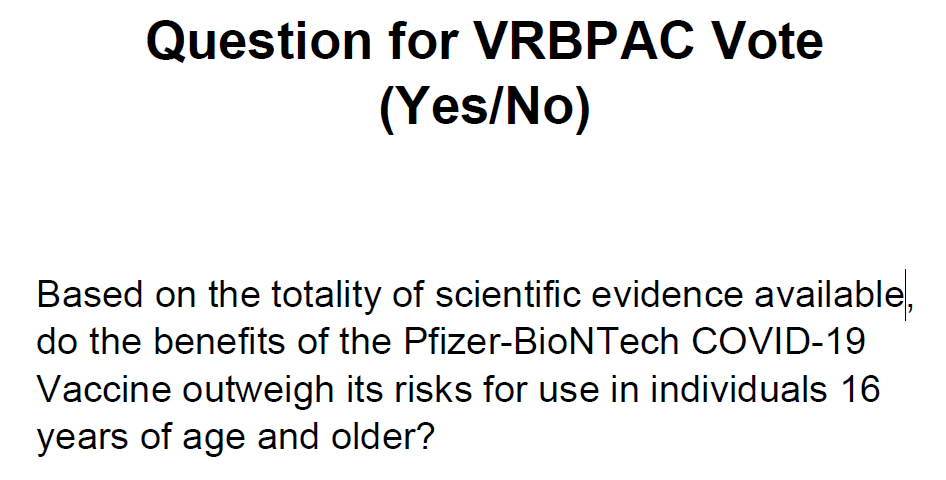

Pfizer [3] published (29) the initial results from its pivotal trial of its COVID-19 vaccine in the NEJM on December 10, 2020, the same day the VRBPAC was convened to discuss its authorization. The protocol for the study was provided as an online supplement to the publication. The protocol Amendment 7, in the version dated October 6, 2020 (p131/376) “Added an additional exploratory objective to describe safety and immunogenicity in participants 16 to 55 years of age vaccinated with study intervention produced by manufacturing ‘Process 1’ or ‘Process 2.’

The protocol elaborates (p174/376): “The initial BNT162b2 was manufactured using “Process 1”, however “Process 2” was developed to support increased scale of manufacture. In the study, each lot of “Process 2” manufactured BNT162b2 will be administered to approximately 250 participants 16 to 55 years of age. The safety and immunogenicity of prophylactic BNT162b2 in individuals 16 to 55 years of age vaccinated with “Process 1” and each lot of “Process 2” study intervention will be described. A random sample of 250 participants from those vaccinated with study intervention by manufacturing “Process 1” will be selected for this descriptive analysis.”

It is now public knowledge that Pfizer’s Process 1 used a DNA template generated by a PCR method, with likely minimal plasmid involvement. Switching to a plasmid – E. coli -based Process 2 similar to the one used by Moderna introduced the possibility of a very different profile of potential impurities and contaminants. These included the starting burden of residual DNA as a process related impurity, the types of DNA (e.g. plasmid sequence elements such as promoters, enhancers, and antibiotic resistance genes), and DNA and endotoxin contaminants from the E. coli . Certainly EMA in their February 19 2021 assessment of the Pfizer product noted (p16/140) that this change “may result in a different impurity profile in the active substance” (30) The “comparability between clinical and commercial material” (p31/140) , along with other issues were the subject of Major Objections (MOs) that would have precluded authorization.

These sorts of process changes introduced a new risk profile to the drug product, that in non-pandemic circumstances would have triggered at least a risk assessment, and possibly an appropriately sized clinical comparability study. FDA’s own guidance entitled “Q5E Comparability of Biotechnological/Biological Products Subject to Changes in Their Manufacturing Process” (31) instructively provides some general principles by which comparability should be determined (emphasis added):

“A determination of comparability can be based on a combination of analytical testing, biological assays, and, in some cases, nonclinical and clinical data. If a manufacturer can provide assurance of comparability through analytical studies alone, nonclinical or clinical studies with the postchange product are not warranted. However, where the relationship between specific quality attributes and safety and efficacy has not been established , and differences between quality attributes of the pre- and postchange product are observed, it might be appropriate to include a combination of quality, nonclinical, and/or clinical studies in the comparability exercise.”

The emboldened clause certainly applies to the modRNA vaccines. Given the necessity for clinical data, to estimate the size of such a study, FDA’s June 2020 guidance “Development and Licensure of Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19” (32) is instructive: “The pre-licensure safety database for preventive vaccines for infectious diseases typically consists of at least 3,000 study participants vaccinated with the dosing regimen intended for licensure.”

This is a far cry from an analysis that is merely “ exploratory ,” “descriptive” and involves only 250 subjects per arm. Perhaps the discrepancy reflects FDA’s switch from the BLA approach described in the June 2020 guidance (32) to an EUA approach in the October guidance. (33) This switch lowered the evidentiary bar from the BLA standard of “established as safe and effective” based on “substantial evidence” “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations.” to the EUA standard of “believes may be effective” based on a “totality of evidence” not requiring clinical studies at all. [4]

Further, an inadequately characterized manufacturing change may have fallen foul of cGMP. This may have been circumvented since. in a public health emergency, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services may “ authorize, with respect to an eligible product, deviations from current good manufacturing practice requirements.” [5] (34) This seems also to have been the approach of EMA who issued a time-limited exemption regarding certain GMP issues that were the subject of Major Objections. This exemption, along with data submitted by Pfizer and the imposition of time-bound “Specific Obligations” (binding conditions to the authorization) and “Recommendations” (not binding but important considerations for future development) allowed EMA to lift the Major Objections and issue its Conditional Market Authorization “ In view of the declared Public Health Emergency of International Concern.” (p32/140 in (30) )

If the Secretary of HHS did issue such a waiver covering matters relating to this sort of process change, VRBPAC members do not appear to have been fully informed either at the meeting of December 10, or the meeting of October 22, 2020 which introduced the EUA framework. FDA’s Dr. Jerry Weir described some of the differences between the cGMP requirements for full (BLA) licensure and the “expectations” under EUA. With the main differences relating to stability and lot release testing, Dr. Weir explained that FDA expected complete details and validation of the manufacturing process, (35) further stating that “ The CMC expectations are very similar for EUA use or licensure.” (p201/408 of transcript (36) ).

Given these representations, the fact of this critical manufacturing change as well as the details of proposed post-authorization requirements or undertakings would be significant components of the “totality of scientific evidence available” VRBPAC was asked to consider when answering FDA’s voting question on December 10, 2020 as to whether or not “the benefits of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine outweigh its risks for use in individuals 16 years of age and older?”

Figure 2 : Voting question for December 10, 2020 VRBPAC meeting [6]

The absence of this information compromises VRBPAC’s ability to assess the benefits and risks associated with the manufacturing change, impugning the integrity and validity of their vote.

Guetzkow and Levi documented Pfizer’s manufacturing changes, relative to the clinical trial and public distribution batches in a Rapid Response published in the British Medical Journal. (37) They described differences in the numbers of adverse events reported to VAERS with various batches and highlighted the “ the importance of publicly disclosing the analysis comparing reactogenicity and safety of process 1 and 2 batches as specified in the trial protocol.”

Further aspects of possible GMP deviations in the use of a “GMP-like” standards ae discussed in section 3.5 . The following questions arise:

Question 23: Did the Secretary of HHS authorize deviations from cGMP regarding the COVID-19 vaccines? Was this a general waiver for all COVID-19 vaccines or for specific vaccines and/or specific issues? Did such a waiver cover any cGMP issues stemming from the Process 1 to Process 2 change for Pfizer’s product?Please provide a copy of all relevant cGMP waivers. Q23

Question 24: When did FDA first learn that Pfizer would be changing from Process 1 to Process 2? Q24

Question 25: After learning about Pfizer’s process change, did FDA consider this change to constitute, absent a comparability analysis, grounds for a non-approvable status or the issuance of something akin to the EMA Major Objection? Q25

Question 26: To what extent did the challenges related to Pfizer’s process change contribute to FDA’s change in regulatory approach from a BLA pathway described in the June 2020 guidance (32) to an EUA pathway describedthe October 2020 guidance (33)? Q26

Question 27: Within the BLA framework described in the June 2020 guidance (32) what comparability requirements did FDA place or would have placed on Pfizer related to the proposed change in manufacturing process? How would these requirements differ under an EUA framework? Q27

Question 28: What combination of provisions, akin to those adopted by EMA, such as GMP waivers, additional pre-EUA data provided by Pfizer, post-EUA obligations and commitments, did FDA make in order to obviate any delays in authorization or approval caused by the process change? Q28

Question 29: Absent these provisions, by how long would the issuance of Pfizer’s EUA have been delayed? Q29

Question 30: Relating to this process change, did FDA request a risk assessment from Prizer? Was one provided and when? Did FDA conduct its own risk assessment? Was any risk assessment addressing this issue, if one exists, disclosed to VRBPAC or publicly. If not please provide. Q30

Question 31: Please confirm that there is no reference to the Process 1 to Process 2 manufacturing change in the meeting materials for the VRBPAC meeting of December 10 2020. Was VRBPAC fully informed of the fact and details of the manufacturing change, including protocol Amendment 7, and if so when and in what form? Q31

Question 32: What was the regulatory basisfor authorizing a process change based on a descriptive comparability analysis involving 250 subjects per arm? Does this analysis meet the BLA “substantial evidence” or merely the EUA “totality of evidence standard”? If the answer is the latter, how is this lowered standard consistent with FDA’s representation in its October 6 2020 (33) guidance and to VRBPAC on October 22, 2020 (38) that it would still require data “from at least one well-designed Phase 3 clinical trial that demonstrates the vaccine’s safety and efficacy in a clear and compelling manner”? Q32

Question 33: Regarding the process change, was VRBPAC fully informed and educated about the lowering of the “substantial evidence” or “clear and compelling” standards to a “totality of evidence” standard? When? In what form? Q33

Question 34: Was VRBPAC fully informed and educated about the existence and details of any cGMP waivers? When and in what form? Other than the publication of Pfizer’s study and protocol in the NEJM[7] on the same day as the VRBPAC meeting, did VRBPAC members receive these materials prior to the December 10 2020 meeting? Q34

3.2. Was the descriptive analysis performed?

Information about the Process 1 to Process 2 change has been more forthcoming from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) than FDA. In its Assessment Report dated February 19 2021, (30) EMA (p34/140) notes the need to demonstrate the biological, chemical and physical comparability of Drug Substance (DS) and Drug Product (DP) produced by the two processes.

“The commercial batches are produced using a different process (Process 2), and the comparability of these processes relies on demonstration of comparable biological, chemical and physical characteristics of the active substance and finished product.”

In relation to this and other issues, EMA (p137/140) determined that “Given the emergency situation, it is considered that the identified uncertainties can be addressed post-authorisation in the context of a conditional MA [marketing authorization],” expecting the descriptive comparability analysis of clinical data in February 2021 ( p69/140).

A heavily redacted comparability report involving bench-top analytical and limited in vitro testing dated March 2021 was released by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in June 2022. (39) However the fate of the clinical descriptive study was not known publicly until the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency’s (MHRA) provided a response to FOI request 23/510. (40)

MHRA explained the need for the descriptive clinical study a little differently from EMA. (30)

“Typically, such changes can be supported by analytical data; however, due to the nascent regulatory landscape for COVID-19 vaccines, in October 2020 an exploratory objective was added in the C4591001 study to describe safety and immunogenicity of vaccines produced by manufacturing “Process 1” or “Process 2” […] ”

Shockingly, MHRA revealed that “this process comparison was not conducted as part of the formal documentation within the protocol amendment.” The study objective that had been added in Amendment 7 in October 2020, had, according to MHRA, been removed in amendment 20 in September 2022 “due to the extensive usage of vaccines manufactured via “Process 2.” “

This episode raises several questions:

Question 35: How many different lots of Process 2 Drug Product (DP) were deployed in Pfizer’s pivotal trial C4591001? How many subjects received Process 2 DP (by lot number)? Q35

Question 36: Please confirm the information provided by MHRA in their FOI response 23/510 that the first subject to receive Process 2 DPdid so on October 18 2020. Please provide the date when the last subject to receive Process 2 DP did so. Q36

Question 37: Please confirm the information provided in EMA’s report (30) that the descriptive clinical comparability analysis was expected in February 2021. If this was not the case, what was the timeline for submission to FDA of Pfizer’s descriptive clinical comparability analysis? Q37

Question 38: What was the regulatory basis for issuing Pfizer’s EUA in the absence of this analysis? Q38

Question 39: What actions did FDA take when Pfizer failed to submit its descriptive clinical comparability analysis by the specified date? Q39

Question 40: What was the regulatory basis for re-issuing Pfizer’s EUA with its various amendments including those involving booster shots and new variant versions in the absence of this analysis? Q40

Question 41: Please confirm the information provided by MHRA in their FOI response 23/510 that this analysis was never conducted and submitted to FDA. Q41

Question 42: Please confirm the information provided by MHRA in their FOI response 23/510 that analysis was removed from the protocol in amendment 20 in September 2022. Q42

Question 43: What was the justification provided by Pfizer for not conducting or submitting this analysis? Please confirm that all or part of this justification is similar to that provided by MHRA in their FOI response 23/510 that this was “due to the extensive usage of vaccines manufactured via “Process 2.” Q43

Question 44: Comparing and contrasting with Question 32 and noting FDA’s 1998 (19), 2019 (20), and 2023 (21) guidance documents regarding evidentiary standards for clinical data, what is the regulatory basis for authorizing or approving a vaccine based on only one clinical study of DP made by a process that differs with DP currently used and made by a process for which there is no “substantial evidence” of clinical comparability “consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations.” Q44

Question 45: If FDA is relying on “extensive usage” in a manner apparently similar to MHRA, is this intended to constitute Real World Evidence (RWE) that can support approvals under some circumstances only described in FDA’s September 19 guidance? (21) Has this RWE been subject to the appropriate controls described in a guidance only recently (Aug 30, 2023)? (41) Q45

Question 46: Was Process 2 DP used in any of Pfizer’s other trials or sub-trials? If so, which? Q46

3.3. EMA concerns regarding the Pfizer process and the process change

Although, as mentioned above, EMA in their February 2021 assessment decided that, given the emergency situation, a number of uncertainties would be addressed after issuing a conditional authorization. (30) While EMA determined that comparability between the two processes had been adequately demonstrated, several matters remained sufficiently concerning to impose “Specific Obligations” in addition to a number of “ Recommendations.” Although some matters were later considered resolved by EMA, with some detail being published by Pfizer, (42) this is by no means settled science and their reexamination is warranted in light of recent findings concerning plasmid-derived DNA (section 5 ), frameshift proteins (section 14 ) and lipid nanoparticles, lipid adducts (section 8 ) discussed below.

Pertinent to this discussion of DNA and RNA, EMA had questions, Specific Obligations ( SO ) or Recommendations ( REC ) (p36/140) related to:

· SO1: the poly(A) tail pattern (p19/140)

· SO1: the 5’ cap (p18/140)

· SO2, REC8: mRNA integrity and dsRNA (pp21, 17/140)

· SO1: differences in the pattern and identity of RNA species revealed by electropherogram (p18/140)

Although EMA considered fragmented and truncated RNA unlikely to result in expressed proteins, EMA observed that the lack of experimental data did not permit a definitive conclusion. EMA noted (p137/140): “The high levels of these impurities reflect the instability of RNA resulting in generation of RNA fragments both in the transcription step and thereafter.”

· SO1: the identity and molecular weights of bands of expressed proteins observed in Western Blots; accounting for glycosylation as a source of discrepancies in molecular weight estimates from Western Blots. (p19/140)

· SO3: confirm the consistency of the finished product (commercial scale) manufacturing process (p36/140)

· REC3: Implementation of analytical methods for release testing of enzymes used in the manufacturing process. (p16/140)

· REC4 : Reassessment of the specification for linear DNA template purity and impurities.

· REC7 : The robustness of the DNase digestion step for the control of residual DNA impurities in DS, EMA noted the ongoing studies on this topic. (p17/140)

· REC10 : Suitable assay for biological characterization of protein expression for the active substance (p20/140)

Question 47: Did FDA express any concern to Pfizer about any of the process-related issues identified above, including the poly(A) tail pattern. the 5’ cap, mRNA integrity, dsRNA, the pattern and identity of RNA and truncated or fragmented RNA, and the identity and molecular weights of proteins expressed after modRNA transfection? How were these concerns resolved? What was the timeline of this process from FDA’s first awareness, to FDA’s expression of concern or questions, to Pfizer’s response and to resolution? Q47

Question 48: Were there concerns similar to those listed in Question 47 regarding the Moderna product? Please describe. Q48

Question 49: Was FDA aware of the concerns expressed by EMA or other regulatory agencies on the subjects discussed in Question 47 and the actions they took to address them? When? Was there any consultation or coordination between agencies? Q49

3.4. EMA concerns regarding residual DNA

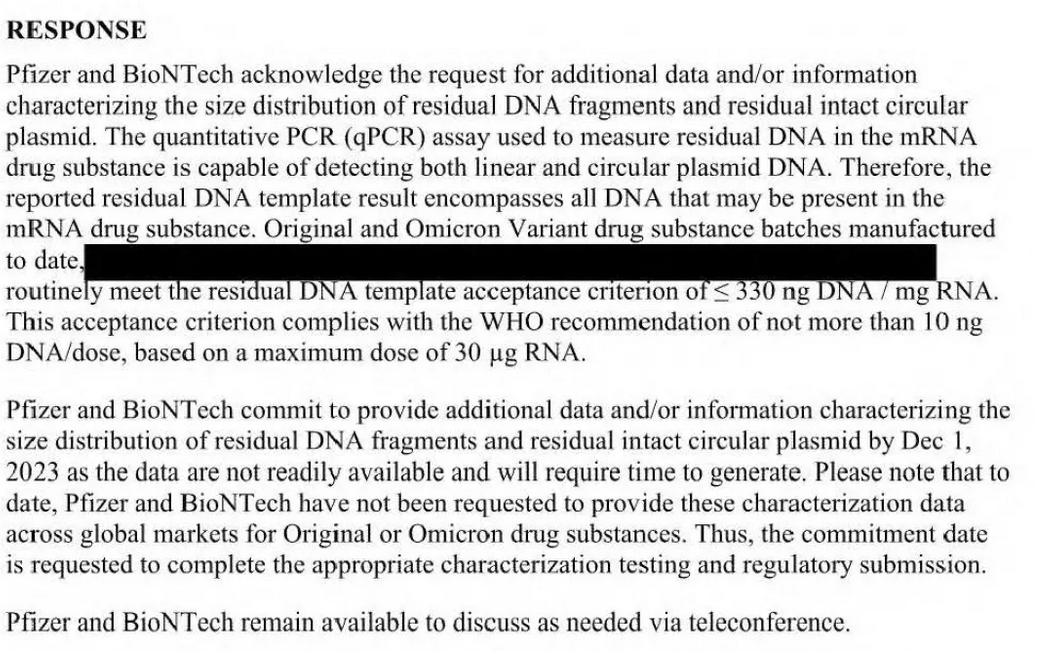

Dr. Marks’ letter makes two statements concerning the removal of residual DNA:

· “As part of the purification process during production, the mRNA is treated with DNAse to digest residual DNA.”

· “The treatment of the products with DNAase also fragments any residual DNA template that might be present after other manufacturing steps.”

No doubt these statements were intended to allay concerns about residual DNA. Dr. Marks’ letter fails to acknowledge that concerns persisted about residual DNA and the DNase digestion step, well past Pfizer’s 2020 EUA and 2021 BLA as revealed in EMA documents.

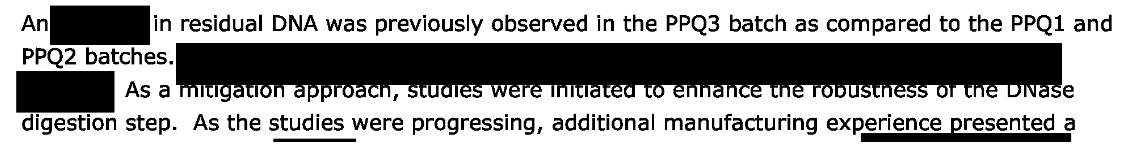

Reports relating to most of EMA’s Specific Obligations (SO) were to be submitted by March 2021. SO3 as well as three (3, 4, 7) of the recommendations from EMA’s February 2021 assessment (30) listed above related in whole or part to various aspects of the DNA template or residual DNA. Two documents released recently pursuant to the European public access regulations (ASK-148075, October 25, 2023) suggest that residual DNA had remained an ongoing issue even to June 2022.

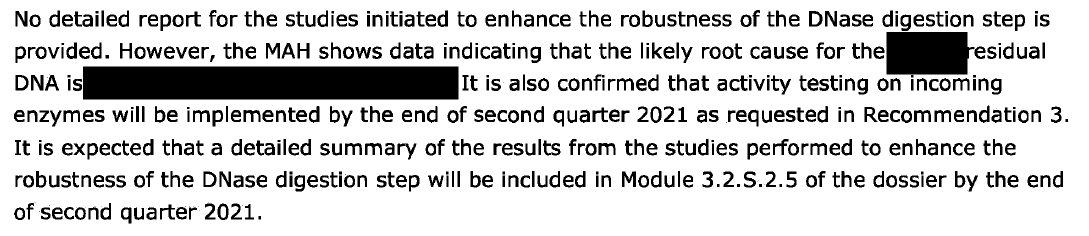

Below are two screen shots from the first of these redacted documents, “CHMP Assessment Report for the Post-Authorisation Measure REC 027, Comirnaty” submitted March 2021 with conclusions adopted May 2021 (43) The redactions are original to the EMA documents as disclosed.

In the context of the third sentence of this first screenshot that begins “As a mitigation approach…” and discusses the robustness of the DNase digestion step , the second word of the paragraph, which, following the word “An,” must begin with a vowel, appears to be ”excess,” “elevation,” or similar.

This is consistent with an unredacted document dated November 25 2020 “ Rapporteur’s Rolling Review assessment report Overview and list of questions. Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/005735/RR.” that states:

"Residual DNA template is present at higher level in PPQ3 [8] batch (211 ng DNA / mg RNA) than in PPQ1 and PQ2 batches (10 and 23 ng/mg); the robustness of DNase I digestion step should be further investigated." (p16/78)

and

“No validation data are available to confirm consistent removal of impurities, which is not acceptable. In addition, residual DNA template is present at higher level in PPQ3 batch (211 ng DNA / mg RNA) than in PPQ1 and PPQ2 batches (10 and 23 ng/mg) which does not confirm the robustness of DNase I digestion.” (p58/78)

This document [9] is among those leaked in December 2020 to several journalists (44) and the BMJ. (45) Given their use by the BMJ, the passage of three years in which the authenticity of the documents could have been challenged, as well as consistency with other documents of known provenance, this document is likely authentic.

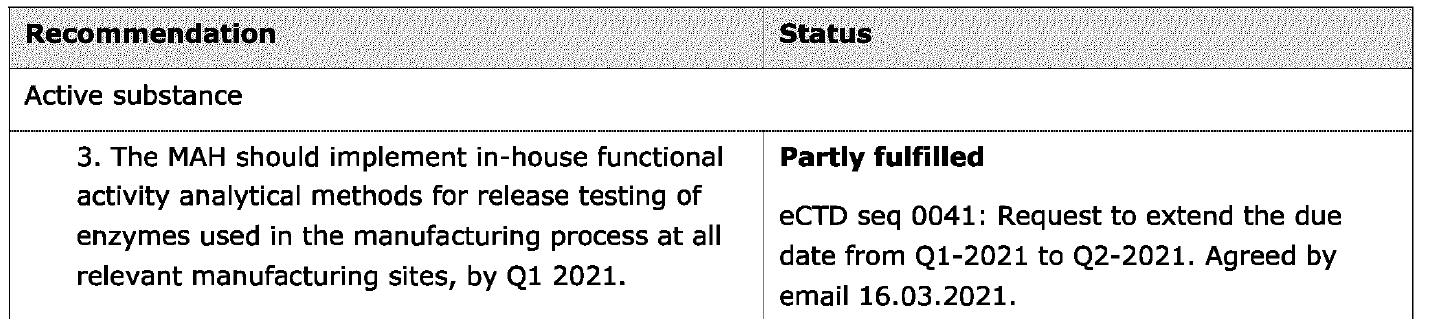

A second screen shot refers to Recommendation 3 ( release testing of enzymes used in the manufacturing process) directly and as a “request” with time frame of 2Q2021.

The words “robustness of the DNase digestion step” is a reference to Recommendation 7. As in the earlier screen shot, the first redaction appears to signal “excess” or similar, or perhaps “variable” or similar. The second redaction appears to be referring to some quality deficiency in the DNase leading to concerning residual DNA levels.

The second document released pursuant to European public access regulations (ASK-148075) is titled “CHMP Type IB variation report, Comirnaty.” (46) The document relates to an application by Pfizer made on January 24 2022 to, inter alia, implement test procedures to qualify DNase used in manufacturing, stemming from Recommendations 3 and 7, to improve the robustness of the DNase digestion step, and therefore result in consistently and acceptably lower levels of residual DNA.

As shown in the screenshots below, the goal of each recommendation was only partly fulfilled. A revised submission was planned for June 2022.

What is most concerning is that some 18 months (at least) after the Pfizer EUA was issued, and about nine months after the COMINARTY BLA was approved, issues with residual DNA still remained.

Question 50: Did FDA express any concern to Pfizer about any issue related to residual DNA such as the robustness of the DNase digestion step. How were these concerns resolved? What was the timeline of this process from FDA’s first awareness, to FDA’s expression of concern or questions, to Pfizer’s response and to resolution? Q50

Question 51: How is the continuing concern well into at least 2022 about residual DNA consistent with the issuance of COMIRNATY’s BLA in August 2021 and the authorization of children’s doses in October 2021? Q51

Question 52: Were there concerns similar to those listed in Question 50 regarding the Moderna product? Please describe. Q52

Question 53: Was FDA aware of the concerns expressed by EMA or other regulatory agencies on the subjects discussed in Question 50 and the actions they took to address them? When? Was there any consultation or coordination between agencies? Q53

3.5. What is “GMP-like”?

Dr. Marks makes two statements that reference the manufacturing process:

· “We would like to make clear that based on a thorough assessment of the entire manufacturing process, FDA is confident in the quality, safety, and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines.”

· “FDA takes its responsibility for ensuring the safety, effectiveness and manufacturing quality of all vaccines licensed in the U.S., including the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, very seriously.”

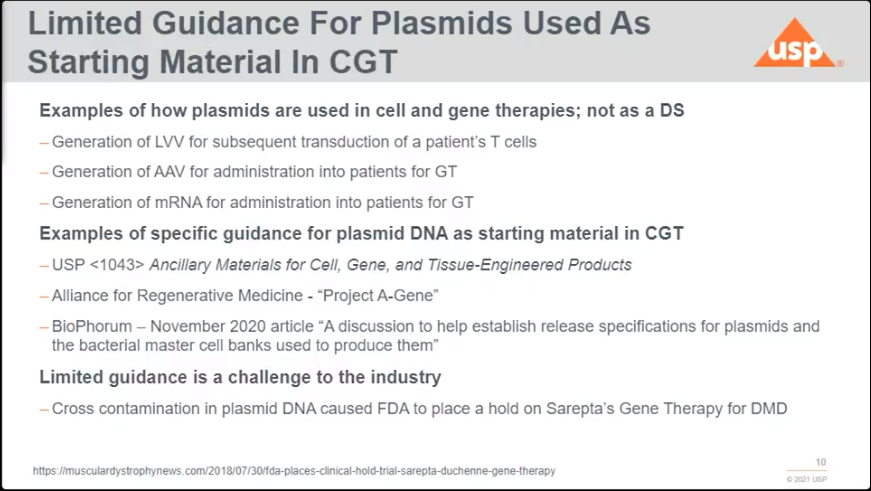

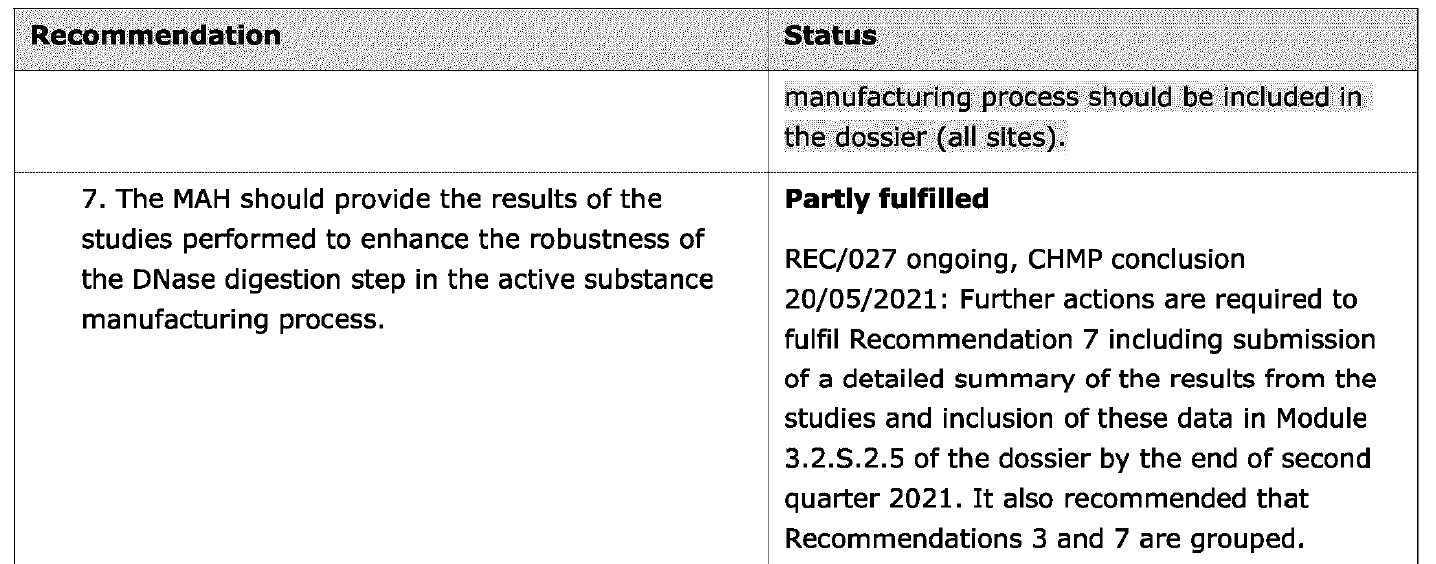

A (June 21 2023) webinar hosted by the USP entitled “ Quality Considerations for Plasmid DNA as a Starting Material for Cell and Gene Therapies” included a presentation by Lawrence Thompson, Associate Research Fellow, Pfizer, and a member of the USP Expert Panel to develop a USP general chapter on “manufacturing and testing of plasmid DNA used as a starting material in the manufacturing of CGT [10] / mRNA products.”

Mr. Thompson discussed the quality of plasmids used in manufacture: [11]

“Then around 2015, we started moving into the gene therapy area, specifically aav gene therapy. And we started working with suppliers who had materials, and they were calling them GMP-like materials, all right, this is sort of a brand new thing that started to pop up. It's not research grade, it's not GMP. What does GMP like even mean? We could talk about that a little more in the discussion section where they have some controls and you need to have some oversight of that. What's the quality of that material? You're going to take a lot of time with supplier knowledge and scientific justification to sort of figure that out. This is when we were working with supplier. Then we started moving internally and making our own stuff, and we had a mix of these different materials. Again, there was a lot of phase-appropriate scientific justification, a lot of discussions about that for this, again, for the gene therapy. Then in 2020, everyone's well aware, we were able to pivot our pipeline from not just gene therapy to mRNA. And there was a whole separate new group of questions that we had to ask ourselves.”

Mr. Thompson revealed that around 2015 suppliers were providing “GMP-like” grade plasmid. From the context of the transcript and the accompanying slide below, it is clear that in 2020 for mRNA manufacturing “GMP-like” plasmid was being used.

Figure 3 : Reference to “GMP-like” in presentation by Pfizer’s Mr. Thompson

Although the presentation and its slide discuss “ phase appropriate scientific justification,” it is unclear what this means.

Question 54: Is FDA aware that “GMP-like” may have been used in the manufacture of Pfizer mRNA? Q54

Question 55: For which phases of Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine preclinical, clinical and post EUA use was “GMP-like” plasmid used? Q55

Question 56: What was the source of Pfizer’s plasmid and its GMP provenance (i.e. GMP, or GMP-like)? Was this obtained from Pfizer’s Gene Therapy Division at the large-scale pDNA manufacturing facility in Chesterfield, MO? Was FDA aware of the source of plasmid? Q56

Question 57: How does “GMP-like” plasmid differ from GMP-compliant plasmid? Q57

Question 58: Regarding the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, for what other preclinical, clinical and post EUA purposes were processes or materials “GMP-like” rather than “GMP compliant? Were these instances of “GMP-like” a reflection of EUA regulations or FDA’s non-enforcement of GMP requirements? Q58

Question 59: Where there any instances of “GMP-like” processes or materials related to the development or manufacturing of the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine? Q59

3.6. Formulation and process changes after nonclinical studies

A number of major and minor changes are known to have been implemented following initial nonclinical studies that could affect a number of quality attributes of modRNA products discussed in this document.

Question 60: For the Pfizer product, which process was used to make the drug product tested in the non-clinical pharmacology and toxicology studies described in the Summary Basis for Regulatory Action. (47) Was test article taken from clinical or commercial scale production material, or from especially conducted non-clinical runs? Q60

Question 61: For the Pfizer product, which non-clinical studies were performed with the V8 version and which with the V9 version? Please confirm that the type made by both Processes 1 and 2 was the V9 type. Q61

Question 62: For both the Pfizer and Moderna products, please summarize and tabulate differences in the composition of Drug Product used in non-clinical, clinical, and post-authorization COVID-10 vaccines, paying particular attention to the modRNA ORF sequence, sequence of non-coding regions, extent and type of nucleoside medication, pattern of codon optimization, LNP and buffer composition. Please indicate the reason for each change and what analytical, non-clinical or clinical comparability studies were performed to qualify these changes. Q62

Question 63: For both the Pfizer and Moderna products, please summarize and tabulate all manufacturing changes from the formulation and process used to produce non-clinical test material to currently produced vaccine that may have changed the amount, type of size distribution of DNA or RNA in the final DP, the amount and type of impurities, as well as critical quality attributes and properties of the LNPs. Please indicate the reason for each change and what analytical, non-clinical or clinical comparability studies were performed to qualify these changes. Q63

The relevance and reliance on supportive studies involving related modRNA products with similar, but not identical compositions will be discussed in sections 11.4.2 and 12.3.1 .

4. Why are the possible harms from residual DNA?

4.1. Prior downgrading of integration risk for residual DNA

Dr. Marks’ non-concern for an integration risk of residual DNA perhaps reflects comments in a 2021 version (48) of the 2007 WHO (49) document addressing DNA vaccines positing that “prior concerns about integration, autoimmunity and immunopathology have not been borne out” and speculating that “the observed reactogenicity appears to relate more to the delivery method than to the DNA vaccine itself, most notably in the case of electroporation or particle-mediated bombardment.” (p14/54)

The downgrading of integration risk has evolved over many years. The 2013 WHO Recommendation document regarding cell substrates for biological products (50) provides an interesting historical perspective on risk assessment related to residual DNA. (p8/110)

In the 1970’s as a result of a clinical research need, interferon alpha (IFN-α) was produced in a tumor line whose cells contained the Epstein-Barr virus genome. With a concern that viral DNA could be transmitted in whole or part to patients, regulatory agencies in several countries authorized human clinical studies and eventually approved an IFN-α product . Contributing to those decisions and the risk-benefit consideration was the fact that the product was being used for therapeutic rather than prophylactic purposes, and that a validated purification process along with assays that could show that DNA was undetectable within the assay limits.

Nonetheless, the same document (50) acknowledged and reviewed the risk of residual DNA en passant (p22/110), citing several papers. (51-55) One particular paper cited, written in 1995 by Petricciani [12] and Horaud (56) is remarkable in that its authors appear to hold, simultaneously contradictory positions that approximate to those at the heart of our current discord.

On the one hand Petricciani and Horaud view DNA and its threats in biologic products in terms of “DNA dragons,” stating that “ many of us believe that we can now see the DNA dragons for what they are: real myths.”

On the other hand, this expression of “belief” appears tempered by its sandwiching between more factual descriptions of the state of science on this topic. This declaration of belief seems to have been precipitated by work bemoaningly cited as demonstrating that an inefficient extraction procedure grossly underestimated the amount of DNA in a biological sample, with the assertion, appropriately, that “ if tests for DNA are to be required, the results should be meaningful rather than fanciful. In other words, the numerical values reported should not be presented simply to provide comfort to regulatory authorities that risk has been reduced, but they should have scientific credibility and be biologically meaningful.”

Petricciani and Horaud concede that “Nevertheless, it also is clear that more needs to be done to achieve a final resolution of the DNA issue. Complex problems are not solved easily or quickly, especially when there is an emotional element overlaid onto scientific issues.” They call for an international group with broad regulatory, industrial, and academic representation to answer questions, including:

· “Is residual cellular DNA a practical and realistic risk, or simply a theoretical concern?

· What range of cellular DNA levels should be considered essentially risk-free?

· What levels of cellular DNA should be considered acceptable as an impurity in biological products?”

In the span of some 30 years and with advances in modRNA and lipid nanoparticle technology, these questions remain as relevant today as in 1995. Most concerning is that Petricciani and Horaud’s motivation in calling for an international group appears to reach a foregone conclusion (theirs) rather than conduct healthy scientific discourse or consider opposing arguments:

“The time is long overdue for sanity to return to the issue of residual cellular DNA in biological products, and for DNA to be treated as a simple impurity rather than as a monster. A conference such as the one proposed above would provide a mechanism to achieve that goal.”

Petricciani and Horaud may well have been correct in their assessment of risks associated with residual DNA resulting from the vaccine technology of the 1990s. But while technology has progressed with innovations in modRNA and LNPs over 30 years, we have not progressed in our ability to grapple with “[c] omplex problems [that] are not solved easily or quickly, especially when there is an emotional element overlaid onto scientific issues.” The time is indeed “long overdue for sanity to return to the issue of residual [cellular] DNA” and that FDA’s detailed answers to the detailed questions posed here, devoid of over-simplification, obfuscation, and thinly veiled accusations of misinformation, will “ provide a mechanism to achieve that goal.”

4.2. Risk of chromosomal integration: nuclear access of DNA

Dr. Marks’ letter makes two statements concerning the plausibility of chromosomal integration of residual DNA, arguing that since access to the nucleus is unlikely, integration is even less likely:

“On first principle, it is quite implausible that the residual small DNA fragments located in the cytosol could find their way into the nucleus through the nuclear membrane present in intact cells and then be incorporated into chromosomal DNA.” (his footnote 2 citing (57) )

“Regarding concern for possible integration of the residual DNA fragments into reproductive cells: Please see the response to the first question above regarding the implausibility that the minute amounts of small DNA fragments present could find their way into the nucleus of these cells.”

These assertions of the implausibility of genomic insertion by residual DNA rely solely on the one reference cite by Dr. Marks as footnote 2 (57) , a chapter in a textbook by Cooper, “The Cell: A Molecular Approach.” The author’s preface reads (emphasis added):

“The goals and distinguishing features of The Cell, however, remain unchanged from the first edition. The Cell continues to be a basic text that provides an accessible introduction for undergraduate or medical students who are taking a first course on cell and molecular biology.”

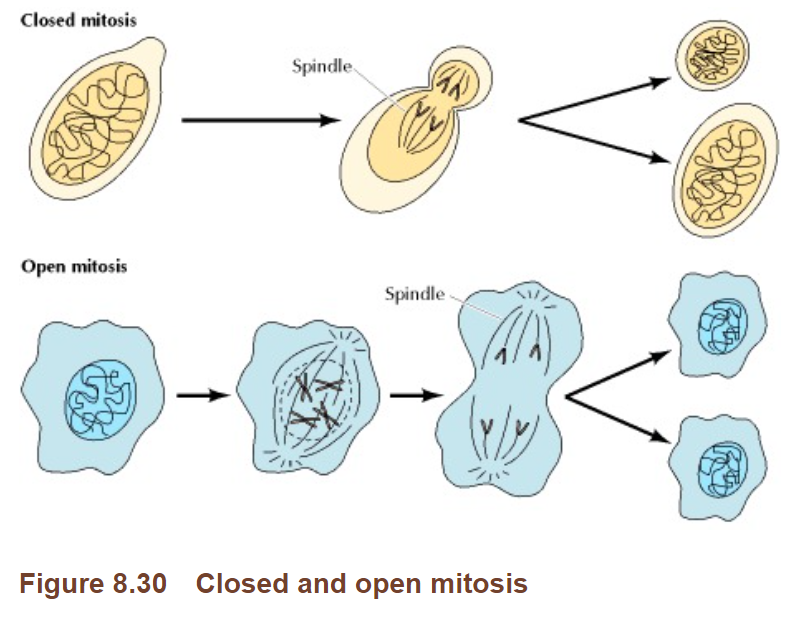

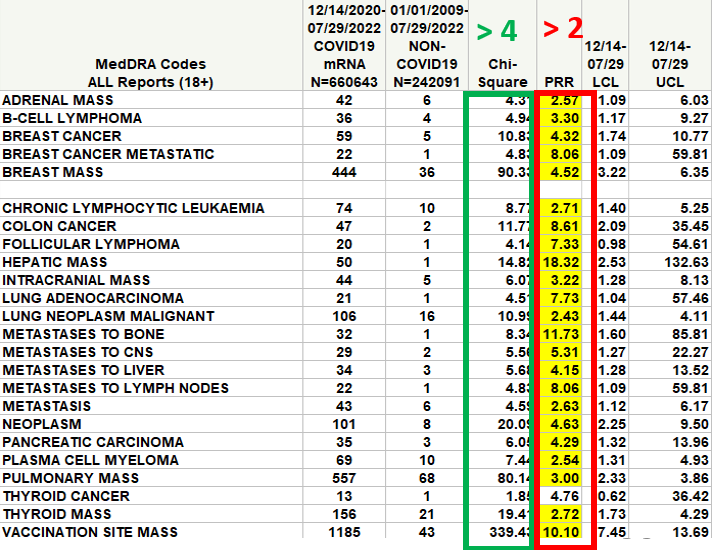

The chapter cited describes the fundamental properties of the nuclear membrane, whose properties are the basis for the assertion as to im plausibility of insertion. It does not discuss the plausibility of nuclear entry or genomic insertion of residual DNA, nor would such a basic introductory undergraduate text be expected to do so. [13] However, from the same basic text book cite by Dr. Marks, another chapter entitled “The Nucleus during Mitosis” (58) renders meaningless the suggestion of “first principle” implausibility of DNA entry by describing how the nuclear membrane breaks down during mitosis, thus plausibly providing access of residual DNA to chromosomal DNA. The chapter states:

“A unique feature of the nucleus is that it disassembles and re-forms each time most cells divide. At the beginning of mitosis, the chromosomes condense, the nucleolus disappears, and the nuclear envelope breaks down , resulting in the release of most of the contents of the nucleus into the cytoplasm .”

Dr. Marks’ statements would in fact be relevant to yeasts, as Cooper elaborates: “ Some unicellular eukaryotes (e.g., yeasts) undergo so-called closed mitosis , in which the nuclear envelope remains intact.” However, as Boettcher and Barral (59) confirm, human cells undergo open mitosis.

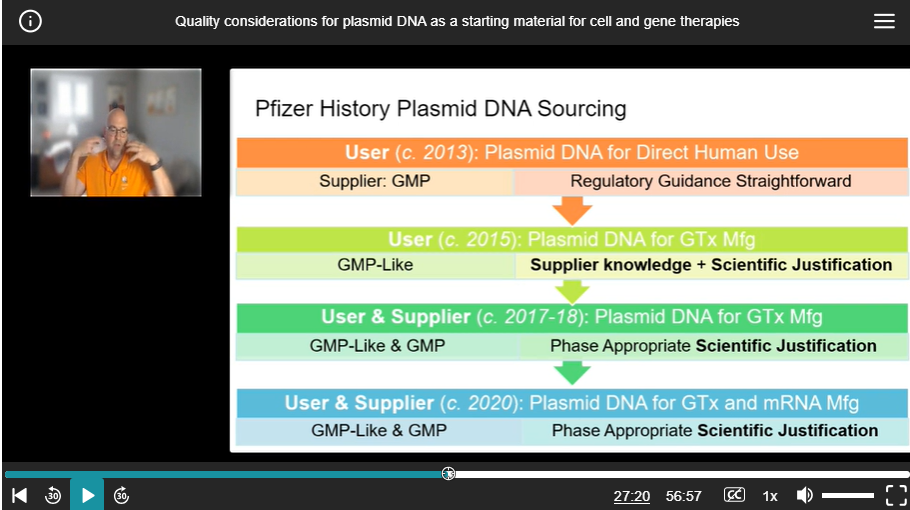

Figure 4 : Figure 8.30 from Cooper

Indeed, Faurez et al., (60) in discussing the biosafety of DNA vaccines and DNA entry into the nucleus, list incorporation of plasmid DNA into the nucleus “ during disassembly of the nuclear membrane during mitosis” as one mechanism, alongside nuclear import by simple or facilitated diffusion through nuclear pores.

Lechardeur et al. (61) review the diffusion of DNA fragments smaller than 250 bp into the nucleus via the Nuclear Pore Complex (NPC).

Question 64: In light of the above review of basic cell biology, and FDA’s “first principle” premise of nuclear membrane inviolability, what studies have FDA conducted or solicited or will FDA be conducting or soliciting from Pfizer and Moderna regarding the intracellular kinetics of residual DNA? Q64

If true, the assertion that DNA could not plausibly even enter the nucleus lacks substance and would render any guidelines concerning residual DNA levels pointless. This assertion is contradicted by the literature showing spontaneous integration after transfection (e.g. (62) ) and self-evident statements about DNA made in several documents authored by FDA, WHO, Moderna or BioNtech (emphasis added):

· FDA 2010 guidance: Characterization and Qualification of Cell Substrates and Other Biological Materials Used in the Production of Viral Vaccines for Infectious Disease Indications (63) (cited in Marks footnote 4)

“Residual DNA might be a risk to your final product because of oncogenic and/or infectivity potential. There are several potential mechanisms by which residual DNA could be oncogenic , including the integration and expression of encoded oncogenes or insertional mutagenesis following DNA integration.” (p40/50)

· FDA 2007 guidance: “Considerations for Plasmid DNA Vaccines for Infectious Disease Indications. Guidance for Industry .” (64) [14]

“Theoretical concerns regarding DNA integration include the risk of tumorigenisis if insertion reduces the activity of a tumor suppressor or increases the activity of an oncogene. In addition, DNA integration may result in chromosomal instability through the induction of chromosomal breaks or rearrangements .” (p9/13)

· WHO 2007 Technical Report Series No 941, Annex 1. Guidelines for assuring the quality and nonclinical safety evaluation of DNA vaccines. (49)

“The injected DNA taken up by cells of the host may integrate into the host's chromosomes and cause an insertional mutagenic event.” (p17/25)

“It is known that DNA taken up by mammalian cells in culture can integrate into the cellular genetic material and be faithfully maintained during replication. This is the basis of the production of some recombinant therapeutic proteins.” (p18/25)

· Sheng-Fowler et al. [FDA staff] Issues associated with residual cell-substrate DNA in viral vaccines. (65)

“The presence of some residual cellular DNA derived from the production-cell substrate in viral vaccines is inevitable. Whether this DNA represents a safety concern, particularly if the cell substrate is derived from a tumor or is tumorigenic, is unknown. DNA has two biological activities that need to be considered. First, DNA can be oncogenic; second, DNA can be infectious/”

· US Patent Application assigned to Moderna US 2019 / 0240317 A1

“The direct injection of genetically engineered DNA (e.g. naked plasmid DNA) into a living host results in a small number of its cells directly producing an antigen, resulting in a protective immunological response. With this technique, however, comes potential problems, including the possibility of insertional mutagenesis , which could lead to the activation of oncogenes or the inhibition of tumor suppressor genes .”

· US Patent assigned to Moderna 2018 US 10,077,439 B2

“The DNA template used in the mRNA manufacturing process must be removed to ensure the efficacy of therapeutics and safety, because residual DNA in drug products may induce activation of the innate response and has the potential to be oncogenic in patient populations. Regulatory guidelines may also require the quantification, control, and removal of the DNA template in RNA products. Currently available or reported methods do not address this deficiency.”

· Sahin [founder BioNTech], Karikó [Nobel Prize 2023] and Türeci “mRNA-based therapeutics -developing a new class of drugs” (66)

“In addition, IVT mRNA-based therapeutics, unlike plasmid DNA and viral vectors, do not integrate into the genome and therefore do not pose the risk of insertional mutagenesis.”

· Dr. Robert Langer [co-founder Moderna] co-author in Reichmuth et al . “mRNA vaccine delivery using lipid nanoparticles” (67)

“mRNA, with the cytosol as its target, is easier to deliver and much safer than DNA, because the mRNA in the cytosol does not interact with the genome in the nucleus and is only transiently expressed. “

There are three other mechanisms whereby DNA might access the nucleus:

· Dalby et al (68) discuss evidence that Lipofectamine 2000, a commonly used laboratory transfectant, may promote “may promote penetration of DNA through intact nuclear envelopes” in some cell types.

· The work of Dr. David Dean at the University of Rochester [15] that focusses on n uclear t argeting of p lasmids and p rotein-DNA c omplexes has shown that t he SV40 enhancer/ promoter/ori sequence facilitates the localization of DNA in the nucleus, “especially in non-dividing cells.” (69, 70) I am informed that this is the same sequence as was found in the Pfizer vaccine (see 7.2 )

· Via a LINE-1 protein product and ribonucleoprotein pathway ( 4.3 ).

Question 65: In light of the above attestations as to the risks of insertional mutagenesis, would FDA revise Dr. Marks’ earlier statement concerning the plausibility of risk of chromosomal integration of residual DNA? Q65

4.3. Additive risks of integration by residual DNA and by DNA reverse transcribed from modRNA

Any risk of integration from residual DNA must be added to the risk associated with DNA produced by reverse transcription of vaccinal modRNA. In a 2022 interview posted on FDA’s Youtube channel, [16] Dr. Marks was asked to comment on “ the thought that vaccines can, particularly with the mRNA, alter one's DNA.” He gave three reasons to support his statement that “there's no way they can alter your DNA”:

· the mRNA is destroyed

· the RNA can't get into the nucleus, the nucleus has a one-way valve

· our cells do not have the enzyme necessary to get RNA back into DNA

These reasons mirror those given in the 2021 WHO guidelines on mRNA vaccines (71) (p47/66) to justify why: “nonclinical studies do not need to be performed to specifically address integration or genetic risks as these are considered to be theoretical issues for mRNA vaccines.” (p48/66)

As will be discussed, none of these arguments hold water, with evidence that these issues are more than “theoretical,” thereby raising concern and the need for studies “ to specifically address integration or genetic risks.”

4.3.1. “the mRNA is destroyed”

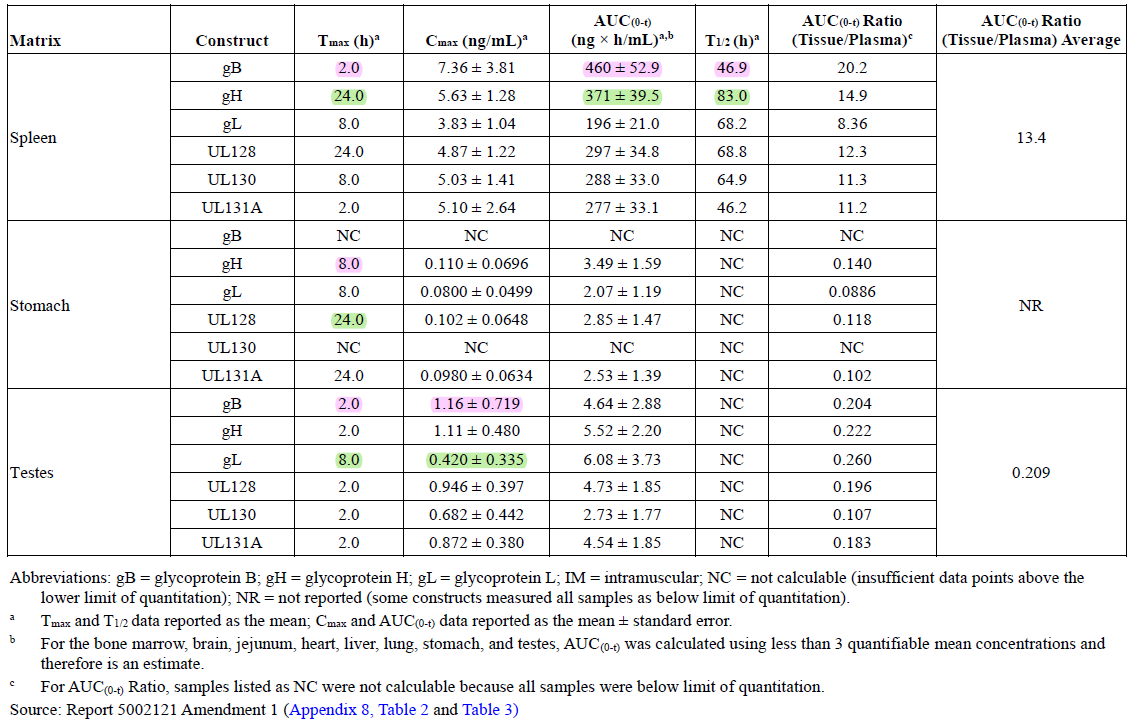

The notion is more fully expressed in the 2021 WHO guidelines on mRNA vaccines (71) : “the vaccine mRNA degrades within a relatively short time once taken up by the body’s cells, as does the cell’s own mRNA. During that entire time, the mRNA vaccine is expected to remain in the cytoplasm, where it will be translated and then degraded by normal cellular mechanisms.” (p48/66)

Although Pfizer did not appear to conduct RNA or protein metabolism studies, a number of reports from animal or human studies have now emerged that detect vaccinal modRNA or spike protein in various tissues weeks or months after vaccination (72-77) , see review in (78) . Based on all of these studies, it is clear that the premise that “mRNA is destroyed” to support the argument that “there's no way [the mRNA vaccines] can alter your DNA” is untenable and at best inconclusive.

Further discussion on the need for biodistribution studies including cellular kinetics of both vaccinal RNA and spike protein, is given in section 0 .

4.3.2. “the RNA can't get into the nucleus, the nucleus has a one-way valve”

Just as nuclear membrane disassembly during mitosis provides access of residual DNA to chromosomal DNA ( 4.2 ), it could apply also to RNA.

An additional potential mechanism is suggested by Sattar whose colleagues include those from NIAID in a work entitled “Nuclear translocation of spike mRNA and protein is a novel pathogenic feature of SARS-CoV-2.” (79) They described how the SARS-Cov-2 spike protein (but not that of other coronaviruses) contains a nuclear localization signal that enables them to translocate into the nucleus in virus-infected cells. Further, they found that spike mRNA also translocates into the nucleus, colocalizing with, and aided by spike protein.

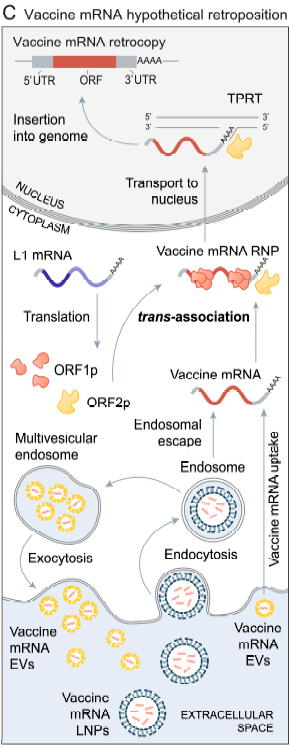

The premise of a “one-way valve” i s subject to challenge for another reason. Citing a rich literature, Domazet-Lošo (80) has reviewed the possibility that mRNA can retropose (undergo r everse transcription to DNA with subsequent insertional mutagenesis, see below) mediated by the protein products of LINE-1. These genes are part of the family of Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements and are considered “Transposable Elements” (TE) because they can transpose from one genomic region to another, modifying its structure and acquiring the name “jumping genes.” (81)

Domazet-Lošo proposes the mechanism illustrated below in which some of the protein products of LINE-1 form ribonucleoprotein complexes with vaccinal mRNA, possibly facilitating its entry to the nucleus, where it can undergo retroposition.

|

|

Figure 5 : Figure 1C and legend from Domazet-Lošo (80) “Hypothetical L1-mediated retroposition of vaccine mRNA. Vaccine mRNA formulated in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) enter the cell via endocytosis. A fraction of the vaccine mRNA enters the cytosol via endosomal escape, while the rest of the vaccine mRNA undergoes degradation in endosomes or is repackaged in multivesicular endosomes into extracellular vesicles (EVs) and secreted back into the extracellular space. The neighboring or distant cells can uptake vaccine mRNA from these EVs. L1 proteins (ORF1p and ORF2p) interact with vaccine mRNA via a process termed trans-association to form a vaccine mRNA ribonucleoprotein particle (vaccine mRNA RNP). Like L1 and parental gene RNPs, a vaccine mRNA RNP enters the nucleus where the vaccine mRNA, through TPRT, is reverse-transcribed and integrated into the genome. The poly-A tail of vaccine mRNA plays a crucial role in this process.” (in text citations removed) |

Question 66: As with conventional pharmacokinetics (PK) (see 0Error! Reference source not found.), a full understanding of the cellular kinetics of any drug is essential to understand its pharmacology and toxicology and is not an academic nicety. What studies will FDA be conducting on its own, or soliciting from Pfizer or Moderna, regarding the intracellular kinetics of modRNA? Q66

4.3.3. “our cells do not have the enzyme necessary to get RNA back into DNA”

The 2021 WHO guideline on mRNA vaccines (71) (p47/66) expresses this premise as “The only known mechanism by which RNA can integrate into the host genome requires the presence of a complex containing reverse transcriptase and integrase.”

This premise is untenable given the reverse transcriptase activity of the protein products of endogenous LINE-1. In his review of retroposition, Domazet-Lošo (80) noted that in addition to the formation of ribonucleoproteins that may facilitate vaccinal modRNA entry into the nucleus, LINE-1 protein products display reverse transcriptase and endonuclease activities. (80) Based on the abundance of LINE-1, and reviewing a number of pertinent factors that could increase retroposition (N-1 methyl pseudouridylation, use of LNP, improved stability, half-life and translational efficiency), Domazet-Lošo voices an “urgent[ly] need [for] experimental studies that would rigorously test for the potential retroposition of vaccine mRNAs. At present, the insertional mutagenesis safety of mRNA-based vaccines should be considered unresolved. ”

Further evidence (see review in (82) ) for the ability of endogenous LINE-1 to effect reverse transcription, and possible insertion comes from the work led by Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch from the Whitehead Institute, MIT and the National Cancer Institute, and funded partly by NIH. (Zhang et al., (83) ) Noting in their introduction, detection of non-retroviral RNA viral sequences into the genomes of many vertebrates, Zhang et al. studied cell lines and patient-derived tissues and found evidence for reverse-transcription of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA and genomic integration by a LINE-1 mechanism. This could result, possibly by template switching, in the production of human-viral mRNA chimeric transcripts and raising the prospect of novel proteins.

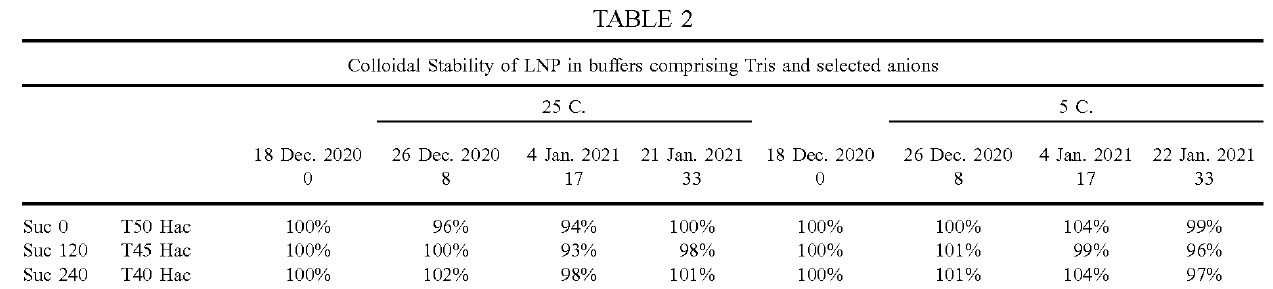

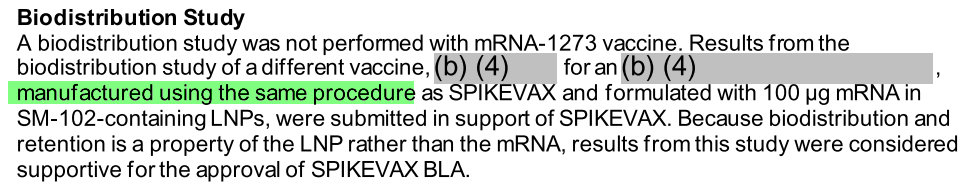

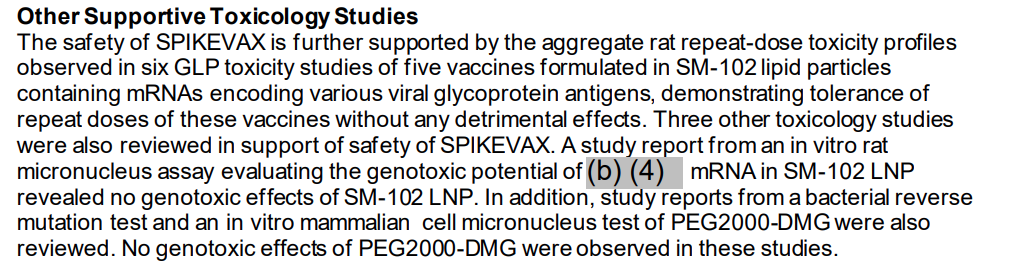

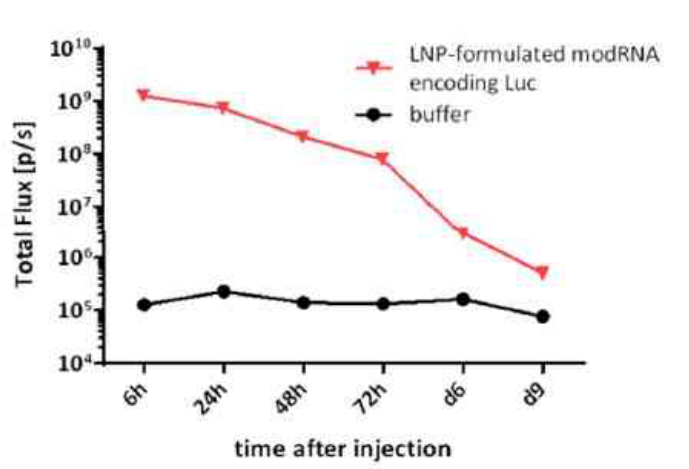

In a subsequent work, the same group reported genomic integration of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA mediated by LINE-1 associated reverse transcription into human cell lines infected with virus, (84) again controverting the premise that “ our cells do not have the enzyme necessary to get RNA back into DNA.” This was not observed for cells transfected with viral RNA. The authors point out a number of limitations to extrapolating their finding to conclude that this would not occur with modRNA vaccines. Firstly, these studies were performed in cell lines and not animals or humans. Secondly, their study achieved transfection using lipofectamine rather than LNPs. Thirdly, the RNA sequence in the study was nucleocapsid and not spike protein. Another important difference was in the sequences of the untranslated regions, the use of N1-methyl pseudouridine and the use of codon of optimization. The findings of Zhang et al. have been challenged, and discussed further by two of the works’ coauthors. (85)